Du Iz Tak? A Lyrical Illustrated Story About the Cycle of Life and the Eternal Equilibrium of Growth and Decay

By Maria Popova

“It is almost banal to say so yet it needs to be stressed continually: all is creation, all is change, all is flux, all is metamorphosis,” Henry Miller wrote in contemplating art and the human future. The beautiful Japanese philosophy of wabi-sabi invites us to find meaning and comfort in impermanence, and yet so much of our suffering stems from our deep resistance to the ruling law of the universe — that of impermanence and constant change. How, then, are we to accept the one orbit we each have along the cycle of life and inhabit it with wholeheartedness rather than despair?

“It is almost banal to say so yet it needs to be stressed continually: all is creation, all is change, all is flux, all is metamorphosis,” Henry Miller wrote in contemplating art and the human future. The beautiful Japanese philosophy of wabi-sabi invites us to find meaning and comfort in impermanence, and yet so much of our suffering stems from our deep resistance to the ruling law of the universe — that of impermanence and constant change. How, then, are we to accept the one orbit we each have along the cycle of life and inhabit it with wholeheartedness rather than despair?

That’s what illustrator and author Carson Ellis explores with great subtlety and warmth in Du Iz Tak? (public library) — a lyrical and imaginative tale about the cycle of life and the inexorable interdependence of joy and sorrow, trial and triumph, growth and decay.

The marvelously illustrated story is written in the imagined language of bugs, the meaning of which the reader deduces with delight from the familiar human emotions they experience throughout the story — surprise, exhilaration, fear, despair, pride, joy. We take the title to mean “What is that?” — the exclamation which the ento-protagonists issue upon discovering a swirling shoot of new growth, which becomes the centerpiece of the story as the bugs try to make sense, then make use, of this mysterious addition to their homeland. “Ma nazoot,” answers another — “I don’t know.”

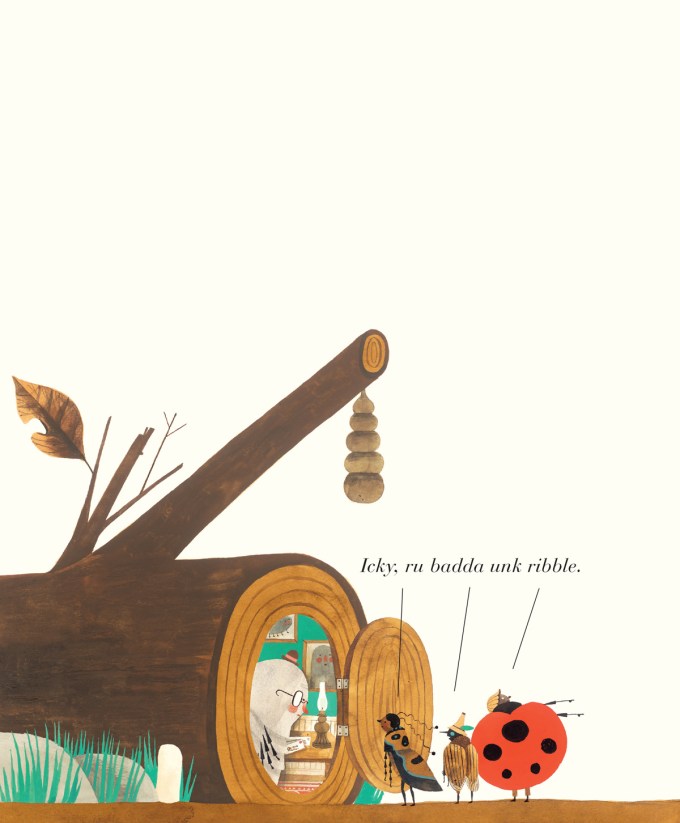

The discoverers of the shoot enlist the help of a wise and many-legged elder who lives inside a tree stump — a character reminiscent in spirit of Owl in Winnie-the-Pooh. He lends the operation his ladder and the team begins building an elaborate fort onto the speedily growing plant.

But their joyful plan is unceremoniously interrupted by a giant spider, who envelops their new playground in a web — a reminder that in nature, where one creature’s loss is another’s gain and vice versa, gain and loss are always counterbalanced in perfect equilibrium with no ultimate right and ultimate wrong.

As the bugs witness the spider’s doing in dejected disbelief, a bird — a creature even huger and more formidable — swoops in to eat the spider and further devastates the stalk-fort. At its base, we see the bugs grow from disheartened to heartbroken.

But when the bird leaves, one of them discovers — with the excited exclamation “Su!,” which we take to mean “Look!” — that the plant has not only survived the invasion but has managed, in the meantime, to produce a glorious, colorful bud.

As the bugs resume repair and construction, the bud blossoms into invigorating beauty. Drawn to the small miracle of the flower, other tiny forest creatures join the joyful labor — the ants interrupt their own industry, the slug slides over in wide-eyed wonder, the bees and the butterflies hover in admiration, and even the elder’s wife emerges from the tree trunk, huffing a pipe as she marvels at the new blossom.

But then, nature once again asserts her central dictum of impermanence and constant change: The flower begins to wilt.

The fort collapses and the bugs, looking not terribly distraught — perhaps because they know that this is nature’s way, perhaps because they know that they too will soon follow the flower’s fate in this unstoppable cycle of life — say farewell and walk off.

Night comes, then autumn, bringing their own magic as the world silently performs its eternal duty of churning the cycle of growth and decay.

The remnants of the wilted flower sink into the forest bed as a nocturnal serenade unfolds overhead before a blanket of snow stills the forest.

In the final pages, we see spring arrive with its redemptive bounty to reveal not one shoot but the promise of an entire flower garden. “Du iz tak?” exclaims a new bug who walks onto the scene — a gentle invitation to reflect on where the others have gone as the seasons turned, presenting a subtle opportunity for parents to broach the cycle of life.

Complement the impossibly wonderful Du Iz Tak? with the Japanese pop-up masterpiece Little Tree — a very different meditation on the cycle of life based on a similar sylvan metaphor — then revisit Ellis’s Home, one of the greatest children’s books of 2015.

All page illustrations © Carson Ellis courtesy of Candlewick Press; photographs by Maria Popova

—

Published December 8, 2016

—

https://www.themarginalian.org/2016/12/08/du-iz-tak-carson-ellis/

—

ABOUT

CONTACT

SUPPORT

SUBSCRIBE

Newsletter

RSS

CONNECT

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

Tumblr