The Little-Known Visual Art of E.E. Cummings

By Maria Popova

“The Artist is no other than he who unlearns what he has learned, in order to know himself,” wrote E.E. Cummings (October 14, 1894–September 3, 1962) — an artist who withstood some spectacularly obtuse criticism for unlearning tradition to press forward with a daring creative vision for the possibilities of language and form that would forever change the landscape of literature. Even the way he signed his name became the subject of controversy and enduring popular misconception. (In fact, contrary to the latter, Cummings himself used both all-lowercase and capitalized versions in signing his work, but capitalized more frequently than not.)

“The Artist is no other than he who unlearns what he has learned, in order to know himself,” wrote E.E. Cummings (October 14, 1894–September 3, 1962) — an artist who withstood some spectacularly obtuse criticism for unlearning tradition to press forward with a daring creative vision for the possibilities of language and form that would forever change the landscape of literature. Even the way he signed his name became the subject of controversy and enduring popular misconception. (In fact, contrary to the latter, Cummings himself used both all-lowercase and capitalized versions in signing his work, but capitalized more frequently than not.)

The poet applied the same ardor for felicitous experimentation to his other great passion: painting, which he considered his “twin obsession,” joining the canon of great writers who were also, unbeknown to most of their readers, pictorial artists — a canon that includes Sylvia Plath’s visual art, Vladimir Nabokov’s butterfly studies, J.R.R. Tolkien’s illustrations, Richard Feynman’s sketches, William Faulkner’s Jazz Age etchings, Flannery O’Connor’s cartoons, and Zelda Fitzgerald’s watercolors.

In a delightful performance of poetic role-play, Cummings contemplated his dual passion in the foreword to a catalogue for the one-man exhibition he had the spring after his fiftieth birthday at the Memorial Gallery in Rochester, New York, later included in E.E. Cummings: A Miscellany Revised (public library) — the out-of-print treasure that gave us Cummings on what it really means to be an artist and his electrifying advice on the courage to be yourself.

In a dialectic prose poem both playful and profound, he sunders himself into critical interlocutor and answering artist — an artist who speaks with the soul-wink of a Zen Buddhist philosopher:

Why do you paint?

For exactly the same reason I breathe.

That’s not an answer.

There isn’t any answer.

How long hasn’t there been any answer?

As long as I can remember.

And how long have you written?

As long as I can remember.

I mean poetry.

So do I.

Tell me, doesn’t your painting interfere with your writing?

Quite the contrary: they love each other dearly.

They’re very different.

Very: one is painting and one is writing.

But your poems are rather hard to understand, whereas your paintings are so easy.

Easy?

Of course — you paint flowers and girls and sunsets; things that everybody understands.

I never met him.

Who?

Everybody.

Did you ever hear of nonrepresentational painting?

I am.

Pardon me?

I am a painter, and painting is nonrepresentational.

Not all painting.

No: housepainting is representational.

And what does a housepainter represent?

Ten dollars an hour.

In other words, you don’t want to be serious —

It takes two to be serious.

Well, let me see… oh, yes, one more question: where will you live after this war is over?

In China; as usual.

China?

Of course.

Whereabouts in China?

Where a painter is a poet.

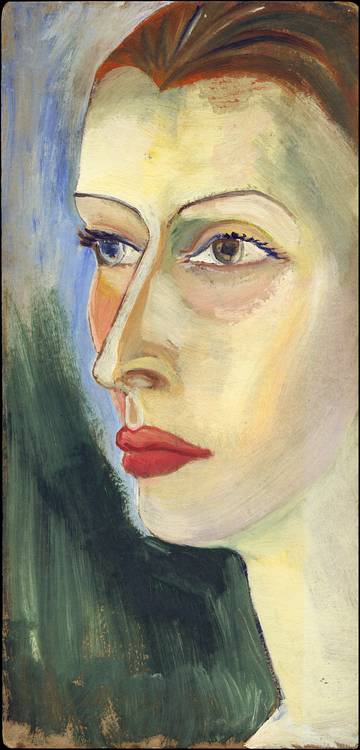

More than seven decades later, the wonderful hope & feathers art gallery in Amherst, Massachusetts, exhibited a selection of Cummings’s sketches, watercolors, and oil paintings, many of them never previously shown. These visual bursts of delight — lightscapes, cloudscapes, treescapes, and many portraits of Marion Morehouse, the love of his life — radiate the same combination of childlike wonder and intensity that marks his poems.

Complement with Cummings’s line drawings and refections on art, then revisit the little-known children’s book he wrote for his only daughter, Amanda Palmer’s beautiful reading of his poem “Humanity i love you”, and an impossibly lovely picture-book celebrating his life and legacy.

Artwork via hope & feathers

—

Published October 5, 2017

—

https://www.themarginalian.org/2017/10/05/e-e-cummings-painting/

—

ABOUT

CONTACT

SUPPORT

SUBSCRIBE

Newsletter

RSS

CONNECT

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

Tumblr