The 7 Loveliest Children’s Books of 2017

By Maria Popova

“Anyone who writes down to children is simply wasting his time,” Charlotte’s Web author E.B. White asserted. “You have to write up, not down.” A generation later, Maurice Sendak scoffed in his final interview: “I don’t write for children. I write — and somebody says, ‘That’s for children!’” Indeed, great children’s books — the timeless kind, which lodge themselves in the marrow of one’s being and seed into the young psyche ideas that bloom again and again throughout a lifetime — radiate a beauty and profundity transcending age. They are books for all of us and for all time.

Here are seven such books published or republished in 2017, to complement the year’s great science books.

BIG WOLF & LITTLE WOLF

We spend our lives trying to discern where we end and the rest of the world begins. There is a strange and sorrowful loneliness to this, to being a creature that carries its fragile sense of self in a bag of skin on an endless pilgrimage to some promised land of belonging. We are willing to erect many defenses to hedge against that loneliness and fortress our fragility. But every once in a while, we encounter another such creature who reminds us with the sweetness of persistent yet undemanding affection that we need not walk alone.

We spend our lives trying to discern where we end and the rest of the world begins. There is a strange and sorrowful loneliness to this, to being a creature that carries its fragile sense of self in a bag of skin on an endless pilgrimage to some promised land of belonging. We are willing to erect many defenses to hedge against that loneliness and fortress our fragility. But every once in a while, we encounter another such creature who reminds us with the sweetness of persistent yet undemanding affection that we need not walk alone.

Such a reminder radiates with uncommon tenderness from Big Wolf & Little Wolf (public library) by French author Nadine Brun-Cosme and illustrator Olivier Tallec, originally published in 2009 and reissued in 2017. With great subtlety and sensitivity, the story invites a meditation on loneliness, the meaning of solidarity, the relationship between the ego and the capacity for love, and the little tendrils of care that become the armature of friendship.

We meet Big Wolf during one of his customary afternoon stretches under a tree he has long considered his own, atop a hill he has claimed for himself. But this is no ordinary day — Big Wolf spots a new presence perched on the horizon, a tiny blue figure, “no bigger than a dot.” With that all too human tendency to project onto the unknown our innermost fears, Big Wolf is chilled by the terrifying possibility that the newcomer might be bigger than he is.

But as the newcomer approaches, he turns out to be Little Wolf.

Big Wolf saw that he was small and felt reassured. He let Little Wolf climb right up to his tree.

“It is a sign of great inner insecurity to be hostile to the unfamiliar,” Anaïs Nin wrote, and it is precisely the stark contrast between Big Wolf’s towering stature and his vulnerable insecurity that lends the story its loveliness and profundity.

At first, the two wolves observe one another silently out of the corner of their eyes. His fear cooled by the smallness and timidity of his visitor, Big Wolf begins to regard him with unsuspicious curiosity that slowly warms into cautious affection. We watch Big Wolf as he learns, with equal parts habitual resistance and sincerity of self-transcendence, a new habit of heart and a wholly novel vocabulary of being.

Night came.

Little Wolf stayed.

Big Wolf thought that Little Wolf went a bit too far.

After all, it had always been his tree.When Big Wolf went to bed, Little Wolf went to bed too.

When Big Wolf saw that Little Wolf was shivering at the tip of his nose, he pushed a teeny tiny corner of his leaf blanket closer to him.“That is certainly enough for such a little wolf,” he thought.

When morning breaks, Big Wolf goes about his daily routine and climbs up his tree to do his exercises, at first alarmed, then amused, and finally — perhaps, perhaps — endeared that Little Wolf follows him instead of leaving.

Once again, Big Wolf at first defaults to that small insecure place, fearing that Little Wolf might outclimb him. But the newcomer struggles, exhaling a tiny “Ouch” as he thuds to the ground on his first attempt before making it up the tree, leaving Big Wolf both unthreatened and impressed with the little one’s quiet courage.

Silently, Little Wolf mirrors Big Wolf’s exercises. Silently, he follows him back down. On the descent, Big Wolf picks his usual fruit for breakfast, but, seeing as Little Wolf isn’t picking any, grabs a few more than usual. Silently, he pushes a modest plate to Little Wolf, who eats it just as silently. The eyes and the body language of the wolves emanate universes of emotion in Tallec’s spare, wonderfully expressive pencil and gouache illustrations.

When Big Wolf goes for his daily walk, he peers at his tree from the bottom of the hill and sees Little Wolf still stationed there, sitting quietly.

Big Wolf smiled. Little Wolf was small.

Big Wolf crossed the big field of wheat at the bottom of the hill.

Then he turned around again.

Little Wolf was still there under the tree.

Big Wolf smiled. Little Wolf looked even smaller.He reached the edge of the forest and turned around one last time.

Little Wolf was still there under the tree, but he was now so small that only a wolf as big as Big Wolf could possibly see that such a little wolf was there.

Big Wolf smiled one last time and entered the forest to continue his walk.

But when he reemerges from the forest by evening, the tiny blue dot is gone from under the tree.

At first, Big Wolf assures himself that he must be too far away to see Little Wolf. But as he crosses the wheat field, he still sees nothing. We watch his silhouette tense with urgency as he makes his way up the hill, propelled by a brand new hollowness of heart.

Big Wolf felt uneasy for the first time in his life.

He climbed back up the hill much more quickly than on all other evenings.There was no one under his tree. No one big, no one little.

It was like before.

Except that now Big Wolf was sad.

“The joy of meeting and the sorrow of separation,” Simone Weil wrote in contemplating the paradox of closeness, “we should welcome these gifts … with our whole soul, and experience to the full, and with the same gratitude, all the sweetness or bitterness as the case may be.” But Big Wolf feels only the bitterness of having lost what he didn’t know he needed until it invaded his life with its unmerited grace.

That evening for the firs time Big Wolf didn’t eat.

That night for the first time Big Wolf didn’t sleep.

He waited.For the first time he said to himself that a little one, indeed a very little one, had taken up space in his heart.

A lot of space.

By morning, Big Wolf climbs his tree but can’t bring himself to exercise — instead, he peers into the distance, his forlorn eyes wide with sorrow and longing.

He bargains the way the bereaved do — if Little Wolf returns, he vows, he would offer him “a larger corner of his leaf blanket, even a much larger one”; he would give him all the fruit he wanted; he would let him climb higher and mirror all of his exercises, “even the special ones known only to him.”

Big Wolf waits and waits and waits, beyond reason, beyond season.

And then, one day, a tiny blue dot appears on the horizon.

For the first time in his life Big Wolf’s heart beat with joy.

Silently, Little Wolf climbs up the hill toward the tree.

“Where were you?” asked Big Wolf.

“Down here,” said Little Wolf without pointing.

“Without you,” said Big Wolf in a very small voice, “I was lonely.”

Little Wolf took a step closer to Big Wolf.

“Me too,” he said. “I was lonely too.”

He rested his head gently on Big Wolf’s shoulder.

Big Wolf felt good.And so it was decided that from then on Little Wolf would stay.

THE PAPER-FLOWER TREE

“The tree which moves some to tears of joy is in the eyes of others only a green thing which stands in the way… As a man is, so he sees,” William Blake wrote in his spectacular 1799 defense of the imagination. More than a century and a half later, illustrator and designer Jacqueline Ayer (May 2, 1930–May 20, 2012) offered a beautiful allegorical counterpart to Blake’s timeless message in her 1962 masterpiece The Paper-Flower Tree (public library) — a warm and whimsically illustrated parable about the moral courage of withstanding cynicism and the generative power of the affectionate imagination.

“The tree which moves some to tears of joy is in the eyes of others only a green thing which stands in the way… As a man is, so he sees,” William Blake wrote in his spectacular 1799 defense of the imagination. More than a century and a half later, illustrator and designer Jacqueline Ayer (May 2, 1930–May 20, 2012) offered a beautiful allegorical counterpart to Blake’s timeless message in her 1962 masterpiece The Paper-Flower Tree (public library) — a warm and whimsically illustrated parable about the moral courage of withstanding cynicism and the generative power of the affectionate imagination.

As vibrant and vitalizing as the tales Ayer imagines in her children’s books is her own true story. Born to first-generation Jamaican immigrants in New York City, Jacqueline grew up in the “Coops” — a communist-inspired cooperative for garment workers in the Bronx. Her father, a graphic artist and the founder of the first licensed modeling agency for black women, taught her to draw. Her mother, a sample cutter, imbued her with an uncommon aptitude for pattern and color. In the 1940s, Jacqueline enrolled in Harlem’s iconic public High School of Music & Art, whose alumni include cartoonist Al Jaffe, graphic designer Milton Glaser, and banjoist Bela Fleck.

After graduating from Syracuse University with a degree in fine art, she continued her studies in Paris, where she became a fashion illustrator and starred in a Dadaist film alongside Man Ray. Her singularly imaginative artwork attracted the attention of designer Christian Dior and Vogue Paris editor Michel de Brunhoff, who procured for her an appointment as fashion illustrator for Vogue in New York. There, she supplemented her meager salary — for those were the days before the Equal Pay uprising that revolutionized the modern workplace, and she was a woman of color — by illustrating for the department store Bonwit Teller alongside young Andy Warhol.

Three years later, Jacqueline went back to Paris on vacation and fell in love with Fred Ayer — a young American who had just returned from Burma and had grown besotted with the cultures of the East. The couple got married and began traveling through East Asia until they finally settled in Thailand, where Ayer raised her two daughters and drew incessantly as she traversed the strange, hot, fragrant wonderland of Bangkok on foot along the sidewalks, on scooter in the streets, on boat via the canals. With support from the Rockefeller Foundation, she launched the fashion and fabric company Design-Thai, which printed her vibrant designs onto silk and cotton using traditional Thai craftsmanship.

Ayer spent the remaining years of her life translating her distinctive aesthetic into home furnishings for New York and London’s glamorous department stores, working for the Indian government under Indira Gandhi to help develop the country’s traditional textile crafts, and creating children’s books of uncommon beauty and emotional intelligence. She was only thirty-one when she won the 1961 Gold Medal of the Society of Illustrators, considered the Oscars of illustration.

The Paper-Flower Tree, originally published in 1962 and now lovingly resurrected by my friends of Brooklyn-based independent powerhouse Enchanted Lion, is one of four books about Thailand Ayer wrote and illustrated, like Tolkien’s Mr. Bliss, for her own children.

It tells the story of a little girl named Miss Moon, who lives under “the enormous blue sky” of rural Thailand and wanders the horizonless rice fields with her baby brother.

One day, a most unusual sight punctuates the noonday torpor of the village. Ayer writes:

Miss Moon saw a little man in the distance, puffing and blowing as he walked slowly along. He carried over his shoulder a bamboo stick, on which were tied colored bits of paper that fluttered in the wind.

Mesmerized by the burst of color, Miss Moon asks the elderly stranger, addressing him with the respectful and affectionate “grandfather,” where he is headed and what marvel he is carrying.

Returning Miss Moon’s affection, the old man addresses her as “little mouse” and explains that he is following the road to wherever it takes him, carrying a paper-flower tree. Ayer writes:

Miss moon smiled. She loved the tree. It was then she knew she had to have one.

“How pretty it is!” she said to the old man. “All those paper flowers twinkling in the sun. I wish I had a tree like that one.”

“One copper coin will buy you two flowers. If one of them has a seed,” the old man said, “who knows? Perhaps you can plant it — perhaps you can grow a tree for yourself.”

But Miss Moon’s heart sinks, for she has not a copper coin. The benevolent stranger meets her sadness with a smile and gives her a paper flower to keep — the smallest one on his tree, but adorned with a tiny black bead on a string — a seed.

He instructs her:

“Plant it — perhaps it will grow. I make no promises. Perhaps it will grow. Perhaps it will not.”

Miss Moon thanked the old man. “Thank you for my tree.”

“It’s not a tree yet; its only a flower, and a paper one at that,” he replied as he waved goodbye.

Much of what makes the story so wonderful is the magical realism of this deliberate interpolation between reality and make-belief — the characters themselves dip in and out of the river of consciousness on the shores of which they are co-creating the half-real, half-imagined miracle of the paper-flower tree, as if to assure us that splendor and delight are only ever the response of consciousness to the world and not a feature of the world itself, no less real, no less splendid or delightful, for being born out of the uncynical imaginations of kindred spirits.

When the old man continues on his open-ended journey, Miss Moon diligently plants the paper-flower seed, builds it a tiny roof to shield it from the unforgiving sun, then begins waiting and watching for it to sprout.

Days and weeks go by, seasons turn, the rice fields change color. Life in the village continues its usual cycle, until a whole year passes — with no paper-flower tree. The other villagers mock Miss Moon’s hopefulness. “You can’t possibly grow a tree from a bead,” they scoff. “You’re wasting your time,” they jeer — responses reminiscent of Leonard Bernstein’s thoughts on the failure of imagination at the heart of cynicism. But Miss Moon remains enchanted by the memory of the beautiful paper-flower tree and resolutely hopeful in her enchantment.

One day, a ramshackle truck rumbles down the road, tooting its horn and kicking up dust.

It rolled into the little village, and — rickety, rackety, crash bam — it came to a stop.

A strange little brown man, dressed in flashy, raggy tatters, hopped up like a bird to the top of the truck.

The odd fellow announces at the top of his lungs that his troupe of musicians and dancers will entertain the people of the village in exchange for a few silver coins.

But then Miss Moon spots amid the performers her old friend — the man with the paper-flower tree. She rushes over and asks “grandfather” if he remembers her. Of course he remembers the “little mouse.” When she laments the fate of her infertile seed, the old man’s face grows sad as he reminds her that he never promised it would grow:

I only said it might grow. Perhaps it won’t, and then again, perhaps it will.

As the spectacle of the circus unfolds into the warm night until the moon sets — drums and cymbals, dancers and clowns, flowing silks and tattered costumes — Miss Moon drifts off to sleep in her own bed and dreams of “bright-light colors and rice fields filled with paper-flower trees.”

When she rises with the sun, awakened by the smell of her mother’s cooking, she steps into the dawn to find aglow in the morning breeze a paper-flower tree.

Just then, she sees the rickety circus truck huffing and puffing away from the village. She runs after it, shouting excitedly at the old man that she finally got her paper-flower tree.

He smiled and waved as the old truck rumbled and roared away.

“Goodbye, little mouse!” he called.

When Miss Moon shows her treasured tree to the other villagers, they dismiss her enthusiasm with the same cynicism — it’s just the old man’s paper flowers on a stick, they say and hasten to remind her that it’s impossible to grow a tree from a bead. But Miss Moon’s radiant joy is undimmed by the cynics — their failure to see the tree as real is their own tragic limitation, and hers is a sovereign joy.

ON A MAGICAL DO-NOTHING DAY

Generations of great thinkers have extolled the creative purpose of boredom. Long before psychologists came to understand why “fertile solitude” is the seedbed of a full life, Bertrand Russell pointed to what he called “fruitful monotony” as central to the conquest of happiness. “There is no place more intimate than the spirit alone,” wrote the poet May Sarton in her stunning 1938 ode to solitude. But today the fertile sanctuary of solitude is a place more endangered than any other locus of the spirit, attesting more acutely than ever to Blaise Pascal’s seventeenth-century assertion that “all of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone.”

Generations of great thinkers have extolled the creative purpose of boredom. Long before psychologists came to understand why “fertile solitude” is the seedbed of a full life, Bertrand Russell pointed to what he called “fruitful monotony” as central to the conquest of happiness. “There is no place more intimate than the spirit alone,” wrote the poet May Sarton in her stunning 1938 ode to solitude. But today the fertile sanctuary of solitude is a place more endangered than any other locus of the spirit, attesting more acutely than ever to Blaise Pascal’s seventeenth-century assertion that “all of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone.”

Now comes a warm and wondrous invitation to remastering the art of fertile solitude in On a Magical Do-Nothing Day (public library) by Italian artist and author Béatrice Alemagna, translated by Jill Davis.

The lyrical, tenderly illustrated story is told in the voice of an androgynous young protagonist who grudgingly accompanies Mom to a writing cabin in the lush, rainy woods — a place oozing boredom only alleviated by a videogame.

Eventually, concerned that this will be “another day of doing nothing,” Mom commands a break from the screen. She confiscates the game and hides it, “as usual,” only to have her discontented child find it, “as usual,” and rush outside in a bright orange raincoat, game tightly clutched as some kind of protective amulet against “this boring, wet place.”

But then, while trying to enact a scene from the game while skipping stones in the pond at the bottom of the path, the reluctant adventurer drops the console into the water and off it plummets to the bottom.

Devastation sets in — now there is nothing to do, nothingness utterly terrifying in thrusting the young protagonist into such sudden solitude with nature.

I was a small tree trapped outside in a hurricane.

The moment of despair is intercepted by a procession of four enormous snails, which offer unexpected delight with their jelly antennae and lead the way to a constellation of mushrooms — a scene that only amplifies the lovely Alice-in-Wonderland undertone of the story.

Small knees drop to the ground and small hands dig into the mud to discover “a thousand seeds and pellets, kernels, grains, roots, and berries” — an underground chest of tactile treasures, pulsating with aliveness that no screen could ever simulate. As though intuiting this awakening of awe, nature turns up the spectacle in a dramatic downpour, sunbeams piercing through the rainclouds to reveal a world seemingly reborn.

With terror now transfigured into newfound mirth, the raincoated explorer surrenders to this strange new wonderland, climbing a tree, drinking raindrops from branches “like an animal would,” marveling at bugs, talking to a bird, wondering:

Why hadn’t I done these things before today?

Upon the triumphant return, soaked to the bone and transformed to the marrow, the young adventurer takes mom’s hand and follows her into the kitchen, where they sit together looking at each other over cups of hot chocolate and savoring the quiet splendor of presence.

That is it. That’s all we did.

On this magical do-nothing day.

BERTOLT

Since long before researchers began to illuminate the astonishing science of what trees feel and how they communicate, the human imagination has communed with the arboreal world and found in it a boundless universe of kinship. A seventeenth-century gardener wrote of how trees “speak to the mind, and tell us many things, and teach us many good lessons.” Hermann Hesse called them “the most penetrating of preachers.” They continue to furnish our lushest metaphors for life and death.

Since long before researchers began to illuminate the astonishing science of what trees feel and how they communicate, the human imagination has communed with the arboreal world and found in it a boundless universe of kinship. A seventeenth-century gardener wrote of how trees “speak to the mind, and tell us many things, and teach us many good lessons.” Hermann Hesse called them “the most penetrating of preachers.” They continue to furnish our lushest metaphors for life and death.

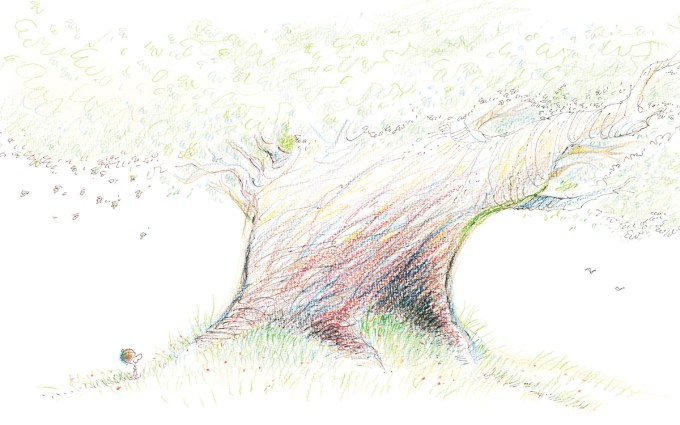

Crowning the canon of arboreal allegories is Bertolt (public library) by French-Canadian geologist-turned-artist Jacques Goldstyn — the uncommonly tender story of an ancient tree named Bertolt and the boy who named and loved it. From Goldstyn’s simple words and the free, alive, infinitely expressive line of his illustrations radiates a profound parable of belonging, reconciling love and loss, and savoring solitude without suffering loneliness.

The story, told in the little boy’s voice, begins with the seeming mundanity of a lost mitten, out of which springs everything that is strange and wonderful about the young protagonist.

He heads to the Lost and Found and walks away with two gloriously mismatched mittens, which give him immense joy but spur the derision of the other boys.

“Sometimes people don’t like what’s different,” he observes with the precocious sagacity of one who knows that other people’s judgements are about them and not about the judged, echoing Bob Dylan’s assertion that “people have a hard time accepting anything that overwhelms them.”

But the little boy is unperturbed — a self-described “loner,” he seems rather centered in his difference and enjoys his solitude.

Unlike the other townspeople, who are constantly doing things together, he is content in his own company — a perfect embodiment of the great film director Andrei Tarkovsky’s advice to the young.

Most of all, the boy cherishes his time with Bertolt — the ancient oak he loves to climb.

After seeing a smaller nearby tree cut down and counting its rings, he estimates that Bertolt is at least 500 years old, inching toward the world’s oldest living trees.

From Bertolt’s branches, which he knows with the intimacy of an old friend, the boy observes the town’s secret life — the lawyer’s daughter kissing the motorcycle bad-boy, the Tucker twins stealing bottles from the grocer and selling them back to him, Cynthia the sheep feasting on a farmer’s corn.

There above and away from the human world, he befriends the animals who have also made a home in Bertolt.

He especially cherishes taking shelter in Bertolt during spring storms. He nestles into Bertolt’s branches, which “sway and creak like the masts of a big ship,” and marvels at how the wind presses flattens the reeds against the ground.

In winter, as he rolls his solitary snowball up the hill, the boy dreams of spring and its promise of kissing Bertolt’s barren branches back to lush life. He relishes the first signs of the season and exults when the trees begin to bloom.

And bloom they do — the lime, the elm, the cherry, the weeping willow.

All except Bertolt.

The boy waits for days, then weeks, his hope vanishing with the passage of time, until one day, with the same precocious sagacity, he accepts that Bertolt is dead.

There is great subtlety in this confrontation with death — a death utterly sorrowful, for the boy is losing his best friend, and yet devoid of the drama of the human world, almost invisible.

He observes that while it is unambiguous when a pet has died, a tree “stands there like a huge boney creature that’s sleeping or playing tricks on us.” If Bertolt had been struck by lightning or chopped off, the boy would have understood. But that a loss so profound can be so undramatic, so uneventful, seems barely comprehensible.

It is this penetrating aspect of the book that places it among the greatest children’s books about processing the subtleties of loss.

Since a burial is impossible, the boy, longing to commemorate Bertolt in some way, eventually dreams up a plan in that combinatorial way in which we fuse our existing experiences into new ideas.

We see him running out of the Lost and Found with a box of colorful mismatched mittens, loading them onto his bike, and racing up the hill toward Bertolt.

With steadfast determination, he climbs the giant trunk, the vibrant load strapped to his back, and begins methodically clipping the mittens to Bertolt’s barren branches with clothespins.

In the final scene, amid the respectful silence of Goldstyn’s unworded illustrations, we see Bertolt half-abloom with mittens. Like Christmas ornaments, like Tibetan prayer flags, they stand as an imaginative replacement for the leaves and blossoms that Bertolt’s fatal final spring failed to bring — not artificial, but realer than anything, for they are made of love.

HERE WE ARE

When the Voyager 1 spacecraft turned its camera back on the Solar System for one last look after taking its pioneering photographs of our planetary neighborhood, it captured a now-iconic image of Earth — a tiny pixel in a tiny slice of an incomprehensibly vast universe. The photograph was christened the “Pale Blue Dot” thanks to Carl Sagan, who immortalized the moment in his timeless monologue on our place in the cosmos:

When the Voyager 1 spacecraft turned its camera back on the Solar System for one last look after taking its pioneering photographs of our planetary neighborhood, it captured a now-iconic image of Earth — a tiny pixel in a tiny slice of an incomprehensibly vast universe. The photograph was christened the “Pale Blue Dot” thanks to Carl Sagan, who immortalized the moment in his timeless monologue on our place in the cosmos:

From this distant vantage point, the Earth might not seem of any particular interest. But for us, it’s different. Consider again that dot. That’s here. That’s home. That’s us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives. The aggregate of our joy and suffering, thousands of confident religions, ideologies, and economic doctrines, every hunter and forager, every hero and coward, every creator and destroyer of civilization, every king and peasant, every young couple in love, every mother and father, hopeful child, inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt politician, every “superstar,” every “supreme leader,” every saint and sinner in the history of our species lived there — on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam.

Forty years after the Voyager sailed into space, we seem to have lost sight of this beautiful and sobering perspective, drifting further and further into our divides, fragmenting our fragile home pixel into more and more warring factions, and forgetting that we are bound together by the improbable miracle of life on this Pale Blue Dot and a shared cosmic destiny.

A mighty antidote to this civilizational impoverishment of imagination comes from Oliver Jeffers, one of the great visual storytellers of our time, in Here We Are: Notes for Living on Planet Earth (public library) — Jeffers’s most personal picture-book yet, dedicated to his firstborn child. (The subtitle, Jeffers said, was inspired by The Universe in Verse, which he attended with his own father.) With expressive illustrations and spare, warm words, Jeffers extends an invitation to all humans, new and old, to fathom the beautiful unity of beings, so gloriously different, orbiting a shared Sun on a common cosmic voyage.

Taking an approach evocative of Charles and Ray Eames’s iconic Powers of Ten, Jeffers zooms from the Solar System to Earth to the city to its living kaleidoscope of inhabitants to the single home where a newborn is meeting the world for the first time, illustrating the intricate interconnectedness of life across all scales of existence.

On our planet, there are people.

One people is a person.

You are a person. You have a body.[…]

People come in many shapes, sizes and colors.

We may all look different, act different and sound different … but don’t be fooled, we are all people.

In the final pages, we see the new father embrace his cocooned child as the whole of humanity stretches into infinity in a colorful waiting line of helpers, reminding us that it takes a village — our global village — to nurture any one life on Earth.

SUN AND MOON

“The dark body of the Moon gradually steals its silent way across the brilliant Sun,” Mabel Loomis Todd wrote in her poetic nineteenth-century masterpiece on the surreal splendor of a total solar eclipse. Nearly a century earlier, in his taxonomy of the three layers of reality, John Keats listed among “things real” the “existences of Sun Moon & Stars and passages of Shakespeare.” Indeed, the motions of the heavenly bodies precipitated the Scientific Revolution that strengthened humanity’s grasp of reality by dethroning us from the center of the universe. But, paradoxically, the Sun and the Moon belong equally with the world of Shakespeare, with humanity’s most enduring storytelling — they are central to our earliest sky myths in nearly every folkloric tradition, radiating timeless stories and parables that give shape to the human experience through imaginative allegory.

“The dark body of the Moon gradually steals its silent way across the brilliant Sun,” Mabel Loomis Todd wrote in her poetic nineteenth-century masterpiece on the surreal splendor of a total solar eclipse. Nearly a century earlier, in his taxonomy of the three layers of reality, John Keats listed among “things real” the “existences of Sun Moon & Stars and passages of Shakespeare.” Indeed, the motions of the heavenly bodies precipitated the Scientific Revolution that strengthened humanity’s grasp of reality by dethroning us from the center of the universe. But, paradoxically, the Sun and the Moon belong equally with the world of Shakespeare, with humanity’s most enduring storytelling — they are central to our earliest sky myths in nearly every folkloric tradition, radiating timeless stories and parables that give shape to the human experience through imaginative allegory.

In Sun and Moon (public library), ten Indian folk and tribal artists bring to life the solar and lunar myths of their indigenous traditions in stunningly illustrated stories reflecting on the universal themes of life, love, time, harmony, and our eternal search for a completeness of being.

This uncommon hand-bound treasure of a book, silkscreened on handmade paper with traditional Indian dyes, comes from South Indian independent publisher Tara Books, who for the past decades have been giving voice to marginalized art and literature through a commune of artists, writers, and designers collaborating on books handcrafted by local artisans in a fair-trade workshop in Chennai, producing such treasures as The Night Life of Trees, Drawing from the City, Creation, and Hope Is a Girl Selling Fruit.

Among the indigenous traditions represented in the book are Gondi tribal art by Bhajju Shyam (of London Jungle Book fame), Durga Bai (featured in The Night Life of Trees), and Ramsingh Urveti (of I Saw a Peacock with a Fiery Tail); Madhubani folk art by Rhambros Jha (of Waterlife); and Meena tribal art by Sunita (of Gobble You Up).

THE BLUE SONGBIRD

“This is the entire essence of life: Who are you? What are you?” young Tolstoy wrote in his diary. A generation later on the other side of the Atlantic, pioneering astronomer Maria Mitchell wrote in hers as she contemplated the art of knowing what to do with one’s life: “To know what one ought to do is certainly the hardest thing in life. ‘Doing’ is comparatively easy.”

“This is the entire essence of life: Who are you? What are you?” young Tolstoy wrote in his diary. A generation later on the other side of the Atlantic, pioneering astronomer Maria Mitchell wrote in hers as she contemplated the art of knowing what to do with one’s life: “To know what one ought to do is certainly the hardest thing in life. ‘Doing’ is comparatively easy.”

How we arrive at that secret and sacred knowledge is what Brooklyn-based artist Vern Kousky explores in The Blue Songbird (public library) — a lyrical and tenderhearted parable about finding one’s voice and coming home to oneself. With its soft watercolors and mellifluous prose composed of simple words, Kousky’s story emanates a Japanese aesthetic of thought and vision, where great truths are surfaced with great gentleness and simplicity.

We meet a a young blue songbird on a golden island, who listens to her sisters’ beautiful songs each morning. Unable to sing like they sing, she anguishes that there seem to be no songs for her in the world.

Her wise and loving mother counsels the blue songbird to “go and find a special song” that she alone can sing.

As though animated by Nietzsche’s proclamation that “no one can build you the bridge on which you, and only you, must cross the river of life,” the blue songbird sets out to cross land and sea in search of her singular song.

After tireless and courageous flight, she reaches a faraway land where she meets a long-necked crane and asks him whether he might know what song she should sing.

The crane, bereft of an answer, points her to the distant mountains perched at the horizon, home to “the wisest bird,” who might know.

She soars over the peaks and finds the wise old bird in the depths of a dark forest. But the owl hoots unknowing, and the blue songbird flies forth on her quest.

Across varied landscapes and foreign lands, the young seeker inquires all she meets whether they might know where her song resides, but no one has the answer.

Kousky writes:

One wintry day, she met a bird who looked a little bit mean and more than a little bit hungry. Even so the songbird bravely chirped:

“Please don’t eat me, Mr. Scary Bird. I just wondered if you’ve ever heard of a very special thing — a song that only I can sing.”

The scary-looking stranger, who turns out to be a kindly crow, finally offers the glimmer of an answer — he doesn’t have her song, but knows where she will find it: She must fly West as far as she can.

And so she does, across the sea, past lighthouses and storm clouds, against mighty winds, until she sees the warm glow of an island “like a jewel on the horizon,” beautiful music flowing from it.

Elated to have made it to her destination, the blue songbird feels a surge of new strength that carries her faster and faster toward the yellow land. But as she swoops down, she realizes that she has returned home.

Just as disappointment is swelling in her chest, she sees her mother and is overcome with the urge to tell her of the crane, and the owl, and the crow, and all the stories of her journey.

But as she opens her beak, what pours out is a song — a song of her very own, about what she had seen and experienced — a testament to Werner Herzog’s conviction that all original art “must have experience of life at its foundation.”

* * *

Step into the cultural time machine with selections for the loveliest children’s books of 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, and 2010.

—

Published December 17, 2017

—

https://www.themarginalian.org/2017/12/17/best-childrens-books-2017/

—

ABOUT

CONTACT

SUPPORT

SUBSCRIBE

Newsletter

RSS

CONNECT

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

Tumblr