A Placid Ecstasy: Walt Whitman’s Most Direct Reflection on Happiness

By Maria Popova

“One can’t write directly about the soul,”, Virginia Woolf wrote. “Looked at, it vanishes.” So with happiness — as slippery as “the soul,” as certain to crumble upon deconstruction. Philosophers have contemplated its nature for millennia, psychologists have attempted to unearth its existential building blocks and delineate its stages. And yet at the heart of it remains a mystery — wildly various across lives and within any one life, a fickle visitation unbeckonable by external lures, as anyone who has sorrowed on a sunny-skied day knows. “There’s no accounting for happiness,” Jane Kenyon wrote in her sublime poem about the ultimate elusion, “or the way it turns up like a prodigal who comes back to the dust at your feet having squandered a fortune far away.”

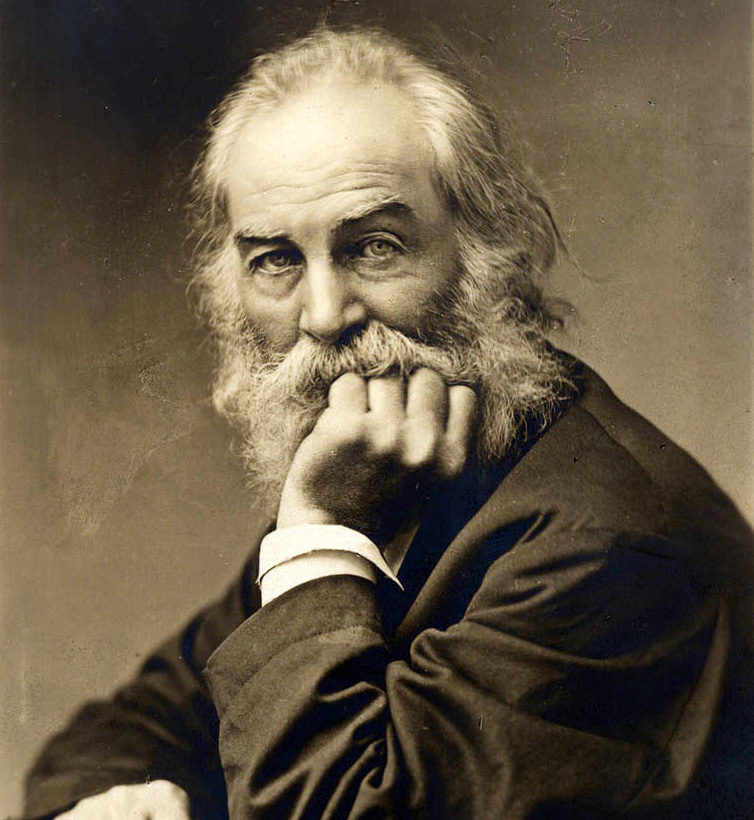

One of the simplest, fullest definitions of happiness I’ve encountered comes from Walt Whitman (May 31, 1819–March 26, 1892) in Specimen Days (public library) — the splendid collection of his prose fragments, letters, and diary entries on subjects like the wisdom of trees, the singular power of music, how art imbues even the bleakest moments with beauty, and what makes life worth living.

In an entry from October 20, 1876, fifty-seven-year-old Whitman composes his most direct meditation on the meaning of happiness. A century before Mary Oliver contemplated what it takes to inhabit a moment of happiness, he writes:

I don’t know what or how, but it seems to me mostly owing to these skies, (every now and then I think, while I have of course seen them every day of my life, I never really saw the skies before,) I have had this autumn some wondrously contented hours — may I not say perfectly happy ones? As I’ve read, Byron just before his death told a friend that he had known but three happy hours during his whole existence. Then there is the old German legend of the king’s bell, to the same point. While I was out there by the wood, that beautiful sunset through the trees, I thought of Byron’s and the bell story, and the notion started in me that I was having a happy hour. (Though perhaps my best moments I never jot down; when they come I cannot afford to break the charm by inditing memoranda. I just abandon myself to the mood, and let it float on, carrying me in its placid extasy.)

What is happiness, anyhow? Is this one of its hours, or the like of it? — so impalpable — a mere breath, an evanescent tinge? I am not sure — so let me give myself the benefit of the doubt.

Complement this particular fragment of the altogether spirit-quenching Specimen Days with Willa Cather’s delicious definition of happiness, Albert Camus on the antidote to its slipperiness, and Agnes Martin on our greatest obstacle to it, then revisit Whitman on how to live a vibrant and rewarding life.

—

Published February 16, 2018

—

https://www.themarginalian.org/2018/02/16/walt-whitman-specimen-days-happiness/

—

ABOUT

CONTACT

SUPPORT

SUBSCRIBE

Newsletter

RSS

CONNECT

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

Tumblr