Little Man, Little Man: James Baldwin’s Only Children’s Book, Celebrating the Art of Seeing and Black Children’s Self-Esteem

By Maria Popova

“The greatest poet in the English language found his poetry where poetry is found: in the lives of the people,” James Baldwin (August 2, 1924–December 1, 1987) wrote in his superbly insightful essay on Shakespeare, language as a tool of love, and the writer’s responsibility in a divided society. But while “the people” of sixteenth-century Europe were very different from the people of twentieth-century America, as were their lives, cultural representations of “the people” of our time and place — of what Whitman celebrated as “a great, aggregated, real PEOPLE, worthy the name, and made of develop’d heroic individuals” — have remained woefully stagnant and unreflective of diversity in the centuries since Shakespeare.

Fifteen years after Gwendolyn Brooks — the first black writer to win a Pulitzer Prize — released her trailblazing poems for kids celebrating diversity and the universal spirit of childhood, Baldwin set out to broaden the landscape of representation in children’s literature by composing a short, playful yet poignant story inspired by his own nephew — Tejan Kafera-Smart, or TJ. Originally published in 1976, with a jacket that billed it as “a child’s story for adults,” Little Man, Little Man: A Story of Childhood (public library) is Baldwin’s addition to the compact canon of sole children’s books composed by literary icons for their own kin, including Sylvia Plath’s The Bed Book, J.R.R. Tolkien’s Mr. Bliss, and William Faulkner’s The Wishing Tree.

The book is less a story than a series of vignettes depicting African American life and childhood on a particular block on New York City’s Upper West Side — one that looks “a little like the street in the movies or the TV when the cop cars come from that end of the street and then they come from the other end of the street.” Baldwin, who considered the book a “celebration of the self-esteem of black children,” began working on it shortly after his historic conversation about race with anthropologist Margaret Mead and set out to find the right illustrator for it.

He chose Yoran Cazac, a white French artist he had met more than a decade earlier through a mutual friend — the African American painter Beauford Delaney, who had mentored the young Baldwin and had taught him what it really means to see. When Delaney was diagnosed with schizophrenia and committed to a psychiatric asylum outside of Paris, Baldwin and Cazac rekindled their friendship in this hour of devastation and sorrow, and soon began collaborating on bringing Little Man, Little Man to life.

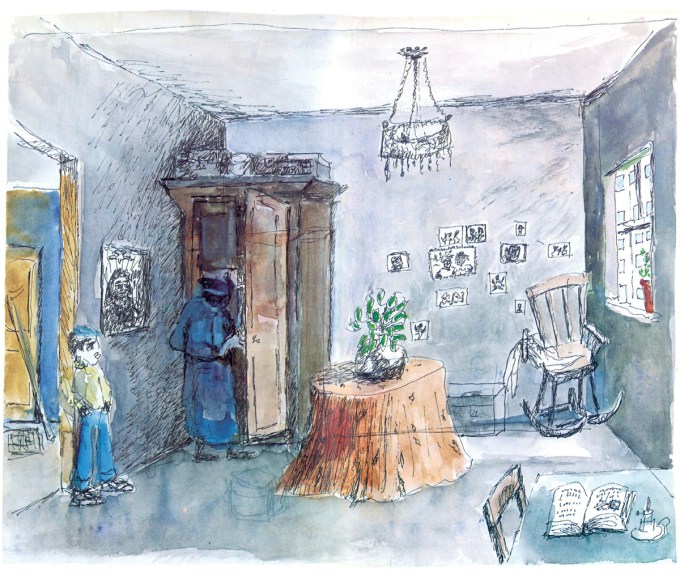

Cazac would complete the art — pencil and watercolor, vibrant and alive, evocative of children’s jubilant and free drawings — without having ever been to Harlem. Instead, Baldwin transported the artist by giving him books on black life, telling him stories about his time in New York, and sharing photographs of his own family there, including his nephew and niece, after whom the characters in the book were modeled. Cazac was determined to “imagine the unimaginable” through these telegraphic descriptions that became a form of artistic telepathy.

The story is written in the authentic colloquial language — children’s language, African American language — of its time and place. It is a creative choice that embodies poet Elizabeth Alexander’s notion of “the self in language” and evokes a sentiment from the stunning speech on the power of language Toni Morrison delivered when she became the first African American woman to win the Nobel Prize in Literature: “We die. That may be the meaning of life. But we do language. That may be the measure of our lives.”

In the introduction to the 2018 edition of Little Man, Little Man, scholars Nicholas Boggs and Jennifer DeVere Brody quote from Baldwin’s essay “If Black English Isn’t a Language, Then Tell Me What Is?”:

It is not the black child’s language that is despised. It is his experience. A child cannot be taught by anyone who despises him, and a child cannot afford to be fooled. A child cannot be taught by anyone whose demand, essentially, is that the child repudiate his experience, and all that gives him sustenance, and enter a limbo in which he will no longer be black, and in which he knows he can never become white. Black people have lost too many children that way.

We meet TJ, just shy of five; his older, bigger friend WT; and Blinky — the bespectacled tomboy who lives with her aunt because “her Mama went away with somebody.” Blinky’s eyeglasses fascinate TJ — he knows that without them, she can barely see, but when he puts them on himself, the world becomes a blur. Even in this subtlest of story-props, Baldwin — who championed the empathic rewards of reading — plants an invitation to empathy rooted in the vital act of taking another’s perspective:

If he can’t see out them, how she going to see out them?

The kids have a way of seeing through the veneers which the adults around them wear to get by in the world. There is Mr. Man, the janitor living in the basement of the brownstone, who is always playing his record player and hardly ever smiles. Behind the frowning life-battered facade, TJ can see a kindly, warmhearted man:

Here he come now, Mr Man, huffing and puffing with them garbage cans, setting them on the side-walk. He try to act like he don’t see TJ. He always try to act like he mean. He ain’t mean, but he getting pretty old, TJ Mama say he got to be about thirty-seven… He don’t hardly never grin, except at TJ and sometime he act like he don’t see him. But TJ know he see him, all the time, even when he look like he ain’t looking, and he even grin at WT and Blinky, too, when he act like he see them. He a real nice man. Sometime he take them down the basement where the furnace is and he tell them stories and he give them ginger snaps and the furnace keep huffing and puffing just like Mr Man with the garbage cans and it get real red hot and Mr Man grin with all them teeth and it real nice then, he a real, real real nice man.

But, in consonance with Neil Gaiman’s insistence that children must not be shielded from dark themes, Baldwin doesn’t sugarcoat the reality of life for the community he depicts in this fictional story. This is a neighborhood strewn with churches and liquor stores, with motherless and fatherless children, where robberies and police chases are a frequent sighting. We gather, though the child reader might not, that Miss Lee — the stunning woman with whom Mr. Man lives and on whom both TJ and WD have a crush — is troubled by depression and addiction:

Sometimes Miss Lee look sad and she walk like she don’t know where she going. But she walk straight. She don’t stagger and stumble. Her eyes is red sometime and she smell strong, like smoke, and sweet, like she been eating peppermint candy, and sometime she smell like licorice. But she always walk straight.

But there is also joy in the neighborhood. The kids pass their time sitting on stoops, playing basketball, skipping rope, and amusing one another with their “African strut.” There are beach trips and delicious Sunday mornings full of laughter and love.

“I want you to be proud of your people,” TJ’s Daddy always say. TJ proud of his people, just like he proud of his Daddy. His Daddy one of them people: they boss people.

Baldwin, who read his way from Harlem to the literary pantheon, celebrates the importance of reading coupled with critical thinking in moving through the world with agency:

TJ’s father read Muhammad Speaks sometime, but then he say, “Don’t believe everything you read. You got to think about what you read.” His Mama say, “But read everything, son, everything you can get your hands on. It all come in handy one day.”

At the heart of the story is a meditation on color — on being black, on the many shades of beauty embedded therein. Baldwin’s description of the different characters’ skin could belong in the pioneering nineteenth-century nomenclature of colors that inspired Darwin: WT is “the color of tea after you put in the milk,” Mr. Man is “the color of chocolate cake without no icing on it,” Miss Lee is “a color like honey and water-melon,” TJ’s mom — “the most beautiful woman in the whole world” — has “skin the color of peaches and brown sugar” and a crown of “coal-black hair,” and Blinky, “she a funny color”:

Her color changing all the time. She always make TJ think of the color of sun-light when your eyes closed and the sun inside your eyes. When your eyes is open, she the color of real black coffee, early in the morning.

Echoing William Blake’s exquisite observation that “the tree which moves some to tears of joy is in the eyes of others only a green thing which stands in the way [for] as a man is, so he sees,” Baldwin touches on this dimensionality of color in recounting the lesson in seeing Delany had taught him:

To stare at a leaf long enough, to try to apprehend the leaf, was to discover many colors in it; and though black had been described to me as the absence of light, it became very clear to me that if this were true, we would never have been able to see the colour; black.

Complement Little Man, Little Man with a lovely contemporary picture-book about how John Lewis’s childhood shaped his civil rights leadership and the darkly philosophical children’s book Toni Morrison wrote with her son, then revisit Baldwin on freedom and how we imprison ourselves, resisting the mindless majority, the artist’s role in society, and “the doom and glory of knowing who you are.”

—

Published October 1, 2018

—

https://www.themarginalian.org/2018/10/01/little-man-little-man-james-baldwin/

—

ABOUT

CONTACT

SUPPORT

SUBSCRIBE

Newsletter

RSS

CONNECT

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

Tumblr