Highlights in Hindsight: Favorite Books of the Past Year

By Maria Popova

I used to assemble annual reading lists of favorite books published each year — never an objective claim of bests, always a subjective inner library catalogue of my readings and rivets. But over the years, as I grew more and more interested in the river of thought and time that has carved out the island of now, I found myself spending more and more time in archives, perusing increasingly older books, reading fewer and fewer of the new — partly because such are my subjective passions (of which The Marginalian has always been a record and reflection), and partly because our present culture seems to treat books as little more than printed “content” (that vacuous term by which we refer to cultural material and thought-matter online), self-referential and preying on the marketable urgencies of the present. With each passing year, more and more books seem to be written and sold as commodities than composed as torches of thought and feeling for our own epoch, but also for epochs to come.

I used to assemble annual reading lists of favorite books published each year — never an objective claim of bests, always a subjective inner library catalogue of my readings and rivets. But over the years, as I grew more and more interested in the river of thought and time that has carved out the island of now, I found myself spending more and more time in archives, perusing increasingly older books, reading fewer and fewer of the new — partly because such are my subjective passions (of which The Marginalian has always been a record and reflection), and partly because our present culture seems to treat books as little more than printed “content” (that vacuous term by which we refer to cultural material and thought-matter online), self-referential and preying on the marketable urgencies of the present. With each passing year, more and more books seem to be written and sold as commodities than composed as torches of thought and feeling for our own epoch, but also for epochs to come.

It is a mercy that there are always those who refuse to conform and go on writing books to irradiate with undiminished light the hallway of time stretching between us and future readers. It is a gift of chance that some of these radiances made their way to my small library. Here are some such books published in the past year that I did read and love, enveloped in the context of why.

PROBABLE IMPOSSIBILITIES

“What exists, exists so that it can be lost and become precious,” Lisel Mueller, who lived to nearly 100, wrote in her gorgeous poem “Immortality” a century and a half after a young artist pointed the world’s largest telescope at the cosmos to capture the first surviving photograph of the Moon and the first-ever photograph of a star: Vega — an emissary of spacetime, reaching its rays across twenty-five lightyears to imprint the photographic plate with a image of the star as it had been twenty-five years earlier, immortalizing a moment already long gone.

“What exists, exists so that it can be lost and become precious,” Lisel Mueller, who lived to nearly 100, wrote in her gorgeous poem “Immortality” a century and a half after a young artist pointed the world’s largest telescope at the cosmos to capture the first surviving photograph of the Moon and the first-ever photograph of a star: Vega — an emissary of spacetime, reaching its rays across twenty-five lightyears to imprint the photographic plate with a image of the star as it had been twenty-five years earlier, immortalizing a moment already long gone.

And yet in a cosmological sense, what exists is precious not because it will one day be lost but because it has overcome the staggering odds of never having existed at all: Within the fraction of matter in the universe that is not dark matter, a fraction of atoms cohered into the elements necessary to form the complex structures necessary for life, of which a tiny portion cohered into the seething cauldron of complexity we call consciousness — the tiny, improbable fraction of a fraction of a fraction with which we have the perishable privilege of contemplating the universe in our poetry and our physics.

In Probable Impossibilities: Musings on Beginnings and Endings (public library), the poetic physicist Alan Lightman sieves four centuries of scientific breakthroughs, from Kepler’s revolutionary laws of planetary motion to the thousands of habitable exoplanets discovered by NASA’s Kepler mission, to estimate that even with habitable planets orbiting one tenth of all stars, the faction of living matter in the universe is about one-billionth of one-billionth: If all the matter in the universe were the Gobi desert, life would be but a single grain of sand.

Along the way, Lightman draws delicate lines of figuring from Hindu cosmology to quantum gravity, from Pascal to inflation theory, from Lucretius to Henrietta Leavitt and Edwin Hubble — lines contouring the most elemental questions that have always animated humanity, questions that are themselves the answer to what it means to be human.

Read more here.

ORWELL’S ROSES

There can be no wakeful and wholehearted devotion to standing for anything of substance — justice or peace or the myriad subtle ways we have of protecting all that is alive and therefore fragile — without wide-eyed, wonder-smitten wakefulness to every littlest manifestation of beauty and aliveness. “Envy those who see beauty in everything in the world,” the young Egon Schiele exhorted in a letter after being arrested for his radical art, hurtling toward an untimely death by the Spanish flu that would take the life of his young pregnant wife three days before taking his.

There can be no wakeful and wholehearted devotion to standing for anything of substance — justice or peace or the myriad subtle ways we have of protecting all that is alive and therefore fragile — without wide-eyed, wonder-smitten wakefulness to every littlest manifestation of beauty and aliveness. “Envy those who see beauty in everything in the world,” the young Egon Schiele exhorted in a letter after being arrested for his radical art, hurtling toward an untimely death by the Spanish flu that would take the life of his young pregnant wife three days before taking his.

There can be no reverence for the timeless without tenderness for each moment beading the rosary of our mortal lives, and there is no place where we contact this more clearly than in our encounters with nature, be it in the majesty of a solar eclipse or in the miniature of a flowerpot. “The gardener digs in another time, without past or future, beginning or end,” the filmmaker and activist Derek Jarman wrote shortly after his HIV diagnosis and his father’s death as he began growing through grief amid the beauty of flowers. “Here is the Amen beyond the prayer.”

Suspended in time between Schiele and Jarman, ablaze with determination to counter the forces about to unworld the world with its deadliest war, George Orwell (June 15, 1903–January 21, 1950) devoted himself to a small, radical act of reverence for beauty.

In the spring of 1936 — while waiting for his beloved to arrive from London for their wedding, contemplating enlisting in the Spanish Civil War, and germinating the ideas that would bloom into Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four — Orwell planted some roses in the garden of the small sixteenth-century cottage that his suffragist, socialist, bohemian aunt had secured for him in the village of Wallington.

This poetic gesture with political roots inspirits the uncommonly wonderful Orwell’s Roses (public library). Like any Rebecca Solnit book, this too is a landmass of layered aboutness beneath the surface story — a book stratified with art and politics, beauty and ecology, mortality and what gives our lives meaning.

She writes:

If war has an opposite, gardens might sometimes be it, and people have found a particular kind of peace in forests, meadows, parks, and gardens.

Three and a half years after he planted them, after thirteen seasons of tending to them, Orwell’s roses bloomed for the first time. World War II had just begun and Ernest Everett Just had just discovered the cellular mechanism by which life begins. It was the year Dylan Thomas wrote his cosmic serenade to trees and what it means to be human and May Sarton penned her exquisite case for the artist’s duty to contact the timeless in tumultuous times, the year the World’s Fair immortalized Einstein’s heavy honey-toned German-Jewish accent in a time-capsule recording, beckoning posterity — that is, us — to defy the mass mentality that leads to war, to mindless consumerism, to the commodification of life itself.

In such a world, a rose is a requiem is a revolution.

Read more here.

ANALOGIA

Long ago, in the ancient bosom of the human animal stirred a quickening of thought and tenderness at the sheer beauty of the world — a yearning to fathom the forces and phenomena behind the enchantments of birdsong and bloom, the rhythmic lapping of the waves, the cottony euphoria of clouds, the swirling patterns of the stars. When we made language to tell each other of the wonder of the world, we called that quickening science.

Long ago, in the ancient bosom of the human animal stirred a quickening of thought and tenderness at the sheer beauty of the world — a yearning to fathom the forces and phenomena behind the enchantments of birdsong and bloom, the rhythmic lapping of the waves, the cottony euphoria of clouds, the swirling patterns of the stars. When we made language to tell each other of the wonder of the world, we called that quickening science.

But our love of beauty grew edged with a lust for power that sent our science on what Bertrand Russell perceptively rued as its “passage from contemplation to manipulation.” The road forked between knowledge as a technology of control and knowledge as a technology of acceptance, of cherishing and understanding reality on its own terms and decoding those terms so that they can be met rather than manipulated.

We went on making equations and theories and bombs in an attempt to control life; we went on making poems and paintings and songs in an attempt to live with the fact that we cannot. Suspended between these poles of sensemaking, we built machines as sculptures of the possible and fed them our wishes encoded in commands, each algorithm ending in a narrowing of possibility between binary choices, having begun as a hopeful verse in the poetry of prospection.

Every writer, if they are lucky enough and passionate enough and dispassionate enough, reads in the course of their lifetime a handful of books they wish they had written. For me, Analogia (public library) by George Dyson is one such book — a book that traverses vast territories of fact and feeling to arrive at a promontory of meaning from which one can view with sudden and staggering clarity the past, the present, and the future all at once — not with fear, not with hope, but with something beyond binaries: with a quickening of wonderment and understanding.

Dyson is a peculiar person to tell the history and map the future of our relationship with technology. Peculiar and perfect: The son of mathematician Verena Huber-Dyson and the philosophically inclined physicist Freeman Dyson, and brother to technology investor and journalist Esther Dyson, George rebelled by branching from the family tree of science and technology at age sixteen to live, as he recounts, “in a tree house ninety-five feet up in a Douglas fir above Burrard Inlet in British Columbia, on land that had never been ceded by its rightful owners, the Tsleil-Waututh.”

In this tree house he built with his own hands, Dyson shared the harsh winters — winters when a cup of tea poured from his perch would freeze before touching the ground — with a colony of cormorants roosting in the nextcrown fir. There, he watched a panoply of seabirds disappear underwater diving after silver swirls of fish he could see in the clear ocean all the way up from the tree. There, he learned to use, and to this day uses, his hands to build kayaks and canoes with the traditional materials and native techniques perfected over millennia. With those selfsame hands, he types these far-seeing thoughts:

There are four epochs, so far, in the entangled destinies of nature, human beings, and machines. In the first, preindustrial epoch, technology was limited to the tools and structures that humans could create with their own hands. Nature remained in control.

In the second, industrial epoch, machines were introduced, starting with simple machine tools, that could reproduce other machines. Nature began falling under mechanical control.

In the third epoch, digital codes, starting with punched cards and paper tape, began making copies of themselves. Powers of self-replication and self-reproduction that had so far been the preserve of biology were taken up by machines. Nature seemed to be relinquishing control. Late in this third epoch, the proliferation of networked devices, populated by metazoan codes, took a different turn.

In the fourth epoch, so gradually that almost no one noticed, machines began taking the side of nature, and nature began taking the side of machines. Humans were still in the loop but no longer in control. Faced with a growing sense of this loss of agency, people began to blame “the algorithm,” or those who controlled “the algorithm,” failing to realize there no longer was any identifiable algorithm at the helm. The day of the algorithm was over. The future belonged to something else.

A belief that artificial intelligence can be programmed to do our bidding may turn out to be as unfounded as a belief that certain people could speak to God, or that certain other people were born as slaves. The fourth epoch is returning us to the spirit-laden landscape of the first: a world where humans coexist with technologies they no longer control or fully understand. This is where the human mind took form. We grew up, as a species, surrounded by mind and intelligence everywhere we looked. Since the dawn of technology, we were on speaking terms with our tools. Intelligence in the cloud is nothing new. To adjust to life in the fourth epoch, it helps to look back to the first.

Read more here.

FUNNY WEATHER

The composite creation of a doctor, a philosopher, a poet, and a sculptor, the word empathy in the modern sense only came into use at the dawn of the twentieth century as a term for the imaginative act of projecting yourself into a work of art, into a world of feeling and experience other than your own. It vesselled in language that peculiar, ineffable way art has of bringing you closer to yourself by taking you out of yourself — its singular power to furnish, Iris Murdoch’s exquisite phrasing, “an occasion for unselfing.” And yet this notion cinches the central paradox of art: Every artist makes what they make with the whole of who they are — with the totality of experiences, beliefs, impressions, obsessions, childhood confusions, heartbreaks, inner conflicts, and contradictions that constellate a self. To be an artist is to put this combinatorial self in the service of furnishing occasions for unselfing in others.

The composite creation of a doctor, a philosopher, a poet, and a sculptor, the word empathy in the modern sense only came into use at the dawn of the twentieth century as a term for the imaginative act of projecting yourself into a work of art, into a world of feeling and experience other than your own. It vesselled in language that peculiar, ineffable way art has of bringing you closer to yourself by taking you out of yourself — its singular power to furnish, Iris Murdoch’s exquisite phrasing, “an occasion for unselfing.” And yet this notion cinches the central paradox of art: Every artist makes what they make with the whole of who they are — with the totality of experiences, beliefs, impressions, obsessions, childhood confusions, heartbreaks, inner conflicts, and contradictions that constellate a self. To be an artist is to put this combinatorial self in the service of furnishing occasions for unselfing in others.

That may be why the lives of artists have such singular allure as case studies and models of turning the confusion, complexity, and uncertainty of life into something beautiful and lasting — something that harmonizes the disquietude and dissonance of living.

In Funny Weather: Art in an Emergency (public library), Olivia Laing — one of the handful of living writers whose mind and prose I enjoy commensurately with the Whitmans and the Woolfs of yore — occasions a rare gift of unselfing through the lives and worlds of painters, poets, filmmakers, novelists, and musicians who have imprinted culture in a profound way while living largely outside the standards and stabilities of society, embodying of James Baldwin’s piercing insight that “a society must assume that it is stable, but the artist must know, and he must let us know, that there is nothing stable under heaven.”

Punctuating these biographical sketches laced with larger questions about art and the human spirit are Laing’s personal essays reflecting, through the lens of her own lived experience, on existential questions of freedom, desire, loneliness, queerness, democracy, rebellion, abandonment, and the myriad vulnerable tendrils of aliveness that make life worth living.

What emerges is a case for art as a truly human endeavor, made by human beings with bodies and identities and beliefs often at odds with the collective imperative; art as “a zone of both enchantment and resistance,” art as sentinel and witness of “how truth is made, diagramming the stages of its construction, or as it may be dissolution,” art as “a direct response to the paucity and hostility of the culture at large,” art as a buoy for loneliness and a fulcrum for empathy.

Laing writes:

Empathy is not something that happens to us when we read Dickens. It’s work. What art does is provide material with which to think: new registers, new spaces. After that, friend, it’s up to you.

I don’t think art has a duty to be beautiful or uplifting, and some of the work I’m most drawn to refuses to traffic in either of those qualities. What I care about more… are the ways in which it’s concerned with resistance and repair.

Read more here.

A SWIM IN A POND IN THE RAIN

We move through a storied world as living stories. Every human life is an autogenerated tale of meaning — we string the chance-events of our lives into a sensical and coherent narrative of who and what we are, then make that narrative the psychological pillar of our identity. Every civilization is a macrocosm of the narrative — we string together our collective selective memory into what we call history, using storytelling as a survival mechanism for its injustices. Along the way, we hum a handful of impressions — a tiny fraction of all knowable truth, sieved by the merciless discriminator of our attention and warped by our personal and cultural histories — into a melody of comprehension that we mistake for the symphony of reality.

We move through a storied world as living stories. Every human life is an autogenerated tale of meaning — we string the chance-events of our lives into a sensical and coherent narrative of who and what we are, then make that narrative the psychological pillar of our identity. Every civilization is a macrocosm of the narrative — we string together our collective selective memory into what we call history, using storytelling as a survival mechanism for its injustices. Along the way, we hum a handful of impressions — a tiny fraction of all knowable truth, sieved by the merciless discriminator of our attention and warped by our personal and cultural histories — into a melody of comprehension that we mistake for the symphony of reality.

Great storytelling plays with this elemental human tendency without preying on it. Paradoxically, great storytelling makes us better able not to mistake our compositions for reality, better able to inhabit the silent uncertain spaces between the low notes of knowledge and the shrill tones of opinion, better able to feel, which is always infinitely more difficult and infinitely more rewarding than to know.

That is what George Saunders explores throughout A Swim in a Pond in the Rain: In Which Four Russians Give a Master Class on Writing, Reading, and Life (public library) — his wondrous investigation of what makes a good story (which is, by virtue of Saunders being helplessly himself, a wondrous investigation of what makes a good life) through a close and contemplative reading of seven classic Russian short stories, examined as “seven fastidiously constructed scale models of the world, made for a specific purpose that our time maybe doesn’t fully endorse but that these writers accepted implicitly as the aim of art — namely, to ask the big questions.” Questions like what truth is and why we love. Questions like how to live and how to make meaning inside the solitary confinement of our mortality. Questions like:

How are we supposed to live with joy in a world that seems to want us to love other people but then roughly separates us from them in the end, no matter what?

Noting that “all coherent intellectual work begins with a genuine reaction,” Saunders frames the central question of his investigation: what we feel and when we feel it, in a story or in the macrocosm of a story that is a life — a framing that calls to mind philosopher Susanne Langer’s notion of music as “a laboratory for feeling in time,” for all great storytelling, as Maurice Sendak observed, is a work of musicality, and all that fills the brief interlude between birth and death is, in anthropologist Mary Catherine Bateson’s lovely phrasing, the work of “composing a life.” In this sense, a story is instrument for feeling — something Saunders places at the heart of his creative theorem:

What a story is “about” is to be found in the curiosity it creates in us, which is a form of caring.

Considering this consonance between storytelling and life, these parallels between how we move through the fictional world of a story and how we move through the real world, Saunders writes:

To study the way we read is to study the way the mind works: the way it evaluates a statement for truth, the way it behaves in relation to another mind (i.e., the writer’s) across space and time… The part of the mind that reads a story is also the part that reads the world; it can deceive us, but it can also be trained to accuracy; it can fall into disuse and make us more susceptible to lazy, violent, materialistic forces, but it can also be urged back to life, transforming us into more active, curious, alert readers of reality.

Dive in here.

THE SNAIL WITH THE RIGHT HEART

Great children’s books move young hearts, yes, but they also move the great common heart that beats in the chest of humanity by articulating in the language of children, which is the language of simplicity and absolute sincerity, the elemental truths of being: what it means to love, what it means to be mortal, what it means to live with our fragilities and our frissons. As such, children’s books are miniature works of philosophy, works of wonder and wonderment that bypass our ordinary resistances and our cerebral modes of understanding, entering the backdoor of consciousness with their soft, surefooted gait to remind us who and what we are.

Great children’s books move young hearts, yes, but they also move the great common heart that beats in the chest of humanity by articulating in the language of children, which is the language of simplicity and absolute sincerity, the elemental truths of being: what it means to love, what it means to be mortal, what it means to live with our fragilities and our frissons. As such, children’s books are miniature works of philosophy, works of wonder and wonderment that bypass our ordinary resistances and our cerebral modes of understanding, entering the backdoor of consciousness with their soft, surefooted gait to remind us who and what we are.

This is something I have always believed, and so I have always turned to children’s books — The Little Prince above all others, for me — as mighty instruments of existential calibration. But I never thought I would write one.

And then I did: The Snail with the Right Heart: A True Story (public library) is a labor of love three years in the making, illustrated by the uncommonly talented and sensitive Ping Zhu.

While the story was inspired by a beloved young human in my own life, born with the same rare and wondrous variation of body as the real-life mollusk protagonist, it is a larger story about science and the poetry of existence, about time and chance, genetics and gender, love and death, evolution and infinity — concepts often too abstract for the human mind to fathom, often more accessible to the young imagination; concepts made fathomable in the concrete, finite life of one tiny, unusual creature dwelling in a pile of compost amid an English garden.

At the heart of the story is an invitation not to mistake difference for defect and to recognize, across the accordion scales of time and space, diversity as nature’s fulcrum of resilience and wellspring of beauty.

Dive in here.

MEDITATIONS: THE ANNOTATED EDITION

The vast majority of our mental, emotional, and spiritual suffering comes from the violent collision between our expectations and reality. As we dust ourselves off amid the rubble, bruised and indignant, we further pain ourselves with the exertion of staggering emotional energy on outrage at how reality dared defy what we demanded of it.

The vast majority of our mental, emotional, and spiritual suffering comes from the violent collision between our expectations and reality. As we dust ourselves off amid the rubble, bruised and indignant, we further pain ourselves with the exertion of staggering emotional energy on outrage at how reality dared defy what we demanded of it.

The remedy, of course, is not to bend the reality of an impartial universe to our will. The remedy is to calibrate our expectations — a remedy that might feel far too pragmatic to be within reach in the heat of the collision-moment, but also one with profound poetic undertones once put into practice, for little syphons the joy of life more surely than the wasted energy of indignation at how others have failed to behave in accordance with what we expected of them.

Few people have understood this more clearly or offered more potent calibration for it than Marcus Aurelius (April 26, 121–March 17, 180).

Two millennia before the outrage culture of the Internet, the lovesick queer teenager turned Roman emperor and Stoic philosopher addressed this curious self-mauling tendency of the human mind with his characteristic precision of insight and unsentimental problem-solving in the notebooks that became his Meditations (public library) — a timeless book, newly translated and annotated by the British classics scholar Robin Waterfield, which Marcus Aurelius wrote largely for and to himself, like Tolstoy wrote his Calendar of Wisdom and Bruce Lee calibrated his core values, yet a book that went on to stake the pillars of the philosophical system of Stoicism, equipping countless generations with tools for navigating the elemental existential challenges of being human and inspiring others to fill the gaps of its unaddressed questions with exquisite answers of their own.

Here is one of my favorite pieces from this new translation.

THE SECRET TO SUPERHUMAN STRENGTH

“Behold, the body includes and is the meaning, the main concern, and includes and is the soul,” Walt Whitman wrote as the Golden Age of Exploration was setting, psychology was beginning to dawn, and the parallel conquests of nature and of human nature were about to converge into their present chaos of humility and hubris. With all the world’s continents “discovered,” with most of the world’s major rivers and mountains measured and mapped, humans began to turn inward, slowly and grudgingly realizing that wherever we go, we take ourselves with us — our selves, those living bodies containing the cosmoses of feeling we call soul.

“Behold, the body includes and is the meaning, the main concern, and includes and is the soul,” Walt Whitman wrote as the Golden Age of Exploration was setting, psychology was beginning to dawn, and the parallel conquests of nature and of human nature were about to converge into their present chaos of humility and hubris. With all the world’s continents “discovered,” with most of the world’s major rivers and mountains measured and mapped, humans began to turn inward, slowly and grudgingly realizing that wherever we go, we take ourselves with us — our selves, those living bodies containing the cosmoses of feeling we call soul.

Since long before we had neuroscience to tell us that our feelings begin in our bodies and shape our consciousness, we humans have been unconsciously using our bodies to control our feelings. And despite our changing ideologies devised to distract from our greatest terror — be they the ancient religious mythologies of immortality or their misshapen rebirth in the modern mythos of productivity — our lives are unconsciously shaped by the fearsome fact of our finitude. Coursing through every moment of being is the awareness, masked and blunted though it may be, that one day we will have been. We cope with it by clinging to the self, building its exoskeleton of achievements and possessions, only to find our inner lives enfeebled by it; only to watch helplessly as the entropic spectacle that governs the universe — the universe of which we are a small and fleeting part — drags our bodies across the stage of the cosmic drama toward oblivion.

And yet, somehow, in the swirl of it all, we go on living. If we are lucky enough, if we are alive enough, we go on making art, making meaning, making an effort to “leave something of sweetness and substance in the mouth of the world.”

We spend our lives trying to discern how to do that and what it all means, trying to illuminate the grand landscape of being with the scattered diffraction of our doings. That touchingly human impulse is what the unclassifiable virtuoso of meaning Alison Bechdel explores in The Secret to Superhuman Strength (public library) — an uncommon beam of illumination, aimed at the depths of existence through the lens of the personal, that one and only lens we ever have on the universe.

Read more and peek inside here.

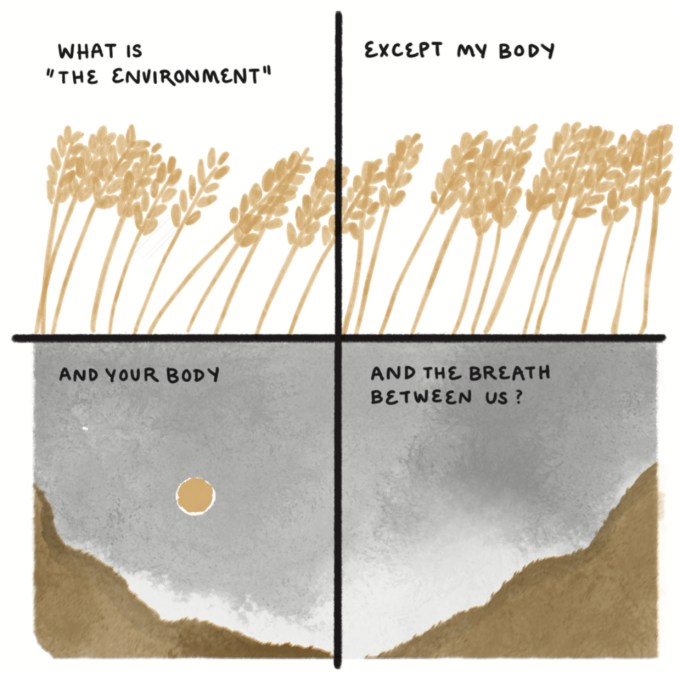

ALL WE CAN SAVE

In 1977, as the Voyager was soaring into the cosmos, about to take that epochal photograph of our home planet viewed from the edge of our Solar System as a “pale blue dot,” in Carl Sagan’s unforgettable poetic phrase, down here on this irreplaceable Earth, Adrienne Rich was writing in the final verse of her poem “Natural Resources”:

In 1977, as the Voyager was soaring into the cosmos, about to take that epochal photograph of our home planet viewed from the edge of our Solar System as a “pale blue dot,” in Carl Sagan’s unforgettable poetic phrase, down here on this irreplaceable Earth, Adrienne Rich was writing in the final verse of her poem “Natural Resources”:

My heart is moved by all I cannot save:

so much has been destroyedI have to cast my lot with those

who age after age, perversely,with no extraordinary power,

reconstitute the world.

This poetic sentiment with powerful resolve became the animating spirit of All We Can Save: Truth, Courage, and Solutions for the Climate Crisis (public library) — Ayana Elizabeth Johnson and Katharine K. Wilkinson’s altogether inspiriting anthology, composed as “a balm and a guide for the immense emotional complexity of knowing and holding what has been done to the world, while bolstering our resolve never to give up on one another or our collective future.”

Rising from the pages are the voices of scientists, activists, poets, policymakers, and other frontier-women decolonizing climate leadership — visionaries united by a fierce willingness to contend with the big, unanswered, often unasked questions that leaven our possible future and to begin answering them in novel ways worthy of a world that prizes creativity over consumption and pluralism over profiteering.

Here is one of my favorite contributions — biomimicry pioneer Janine Benyus on tree islands, networked resilience, and the power of reciprocity in nature.

BEFORE I GREW UP

Childhood is one great brush-stroke of loneliness, thick and pastel-colored, its edges blurring out into the whole landscape of life.

Childhood is one great brush-stroke of loneliness, thick and pastel-colored, its edges blurring out into the whole landscape of life.

In this blur of being by ourselves, we learn to be ourselves. One measure of maturity might be how well we grow to transmute that elemental loneliness into the “fruitful monotony” Bertrand Russell placed at the heart of our flourishing, the “fertile solitude” Adam Phillips recognized as the pulse-beat of our creative power.

If we are lucky enough, or perhaps lonely enough, we learn to reach out from this primal loneliness to other lonelinesses — Neruda’s hand through the fence, Kafka’s “hand outstretched in the darkness” — in that great gesture of connection we call art.

Rilke, contemplating the lonely patience of creative work that every artist knows in their marrow, captured this in his lamentation that “works of art are of an infinite loneliness” — Rilke, who all his life celebrated solitude as the groundwater of love and creativity, and who so ardently believed that to devote yourself to art, you must not “let your solitude obscure the presence of something within it that wants to emerge.”

Giuliano Cucco (1929–2006) was still a boy, living with his parents amid the majestic solitudes of rural Italy, when the common loneliness of childhood pressed against his uncommon gift and the artistic impulse began to emerge, tender and tectonic.

Over the decades that followed, he grew volcanic with painting and poetry, with photographs and pastels, with art ablaze with a luminous love of life.

When Cucco moved to Rome as a young artist, he met the young American nature writer John Miller. A beautiful friendship came abloom. Those were the early 1960, when Rachel Carson — the poet laureate of nature writing — had just awakened the modern ecological conscience and was using her hard-earned stature to issue the radical insistence that children’s sense of wonder is the key to conservation.

Into this cultural atmosphere, Cucco and Miller joined their gifts to create a series of stunning and soulful nature-inspired children’s books.

But when Miller returned to New York, door after door shut in his face — commercial publishers were unwilling to invest in the then-costly reproduction of Cucco’s vibrant art. It took half a century of countercultural courage and Moore’s law for Brooklyn-based independent powerhouse Enchanted Lion to take a risk on these forgotten vintage treasures and bring them to life.

Eager to reconnect with his old friend and share the exuberant news, Miller endeavored to track down Cucco’s family. But when he finally reached them after a long search, he was devastated to learn that the artist and his wife had been killed by a motor scooter speeding through a pedestrian crossing in Rome. Their son had just begun making his way through a trove of his father’s paintings — many unseen by the world, many depicting the landscapes and dreamscapes of childhood that shaped his art.

Because grief is so often our portal to beauty and aliveness, Miller set out to honor his friend by bringing his story to life in an uncommonly original and tender way — traveling back in time on the wings of memory and imagination, to the lush and lonesome childhood in which the artist’s gift was forged, projecting himself into the boy’s heart and mind through the grown man’s surviving paintings, blurring fact and fancy.

Before I Grew Up (public library) was born — part elegy and part exultation, reverencing the vibrancy of life: the life of feeling and of the imagination, the life of landscape and of light, the life of nature and of the impulse for beauty that irradiates what is truest and most beautiful about human nature.

Peek inside here.

BELOVED BEASTS

“Love the earth and sun and the animals,” Walt Whitman instructed in his advice for living a vibrant and rewarding life just before the brokenhearted young marine biologist Ernst Haeckel coined the term ecology. But over the century that followed, the lust for industry and capital became the mating call of the human animal, silencing Whitman’s voice and vanquishing other species. Along the way, a handful of visionaries rose with countercultural courage against the tide of their time and managed to lift the whole of culture along, just enough to see a little more clearly and humbly our place in the family of life on this pale blue dot, and our responsibility to it. We called that vision conservation, but beneath the labels and the language, it is just another way of being fully human.

“Love the earth and sun and the animals,” Walt Whitman instructed in his advice for living a vibrant and rewarding life just before the brokenhearted young marine biologist Ernst Haeckel coined the term ecology. But over the century that followed, the lust for industry and capital became the mating call of the human animal, silencing Whitman’s voice and vanquishing other species. Along the way, a handful of visionaries rose with countercultural courage against the tide of their time and managed to lift the whole of culture along, just enough to see a little more clearly and humbly our place in the family of life on this pale blue dot, and our responsibility to it. We called that vision conservation, but beneath the labels and the language, it is just another way of being fully human.

In Beloved Beasts: Fighting for Life in an Age of Extinction (public library), Michelle Nijhuis undusts the uncommon lives of several of these visionaries — “scientists, birdwatchers, hunters, self-taught philosophers, and others who have countered the power to destroy species with the whys and hows of providing sanctuary” — interleaving their stories into the broader story of conservation. She writes:

Each person profiled here stood, or stands, at a turning point in the story of modern species conservation — a story which, for better and sometimes worse, still guides the international movement to protect life on earth… Though they often used pragmatic arguments to convert others to their cause, their personal motivations ran deeper, for many had started keeping company with members of other species to escape their own troubles. Some were painfully shy, or burdened with mental or physical illness. Some were separated from spouses at a time when divorce was a scandal, or drawn to their own gender when homosexuality was taboo. Most of them knew something about suffering, and they found consolation in the sights and sounds of other forms of life.

[…]

The story of modern species conservation is full of people who did the wrong things for the right reasons, and the right things for the wrong reasons.

Read about one of them — Rosalie Edge, the pioneering conservationist who saved the hawks — here.

THE HUMMINGBIRDS’ GIFT

Frida Kahlo painted a hummingbird into her fiercest self-portrait. Technology historian Steven Johnson drew on hummingbirds as the perfect metaphor for revolutionary innovation. Walt Whitman found great joy and solace in watching a hummingbird “coming and going, daintily balancing and shimmering about,” as he was learning anew how to balance a body coming and going in the world after his paralytic stroke. For poet and gardener Ross Gay, “the hummingbird hovering there with its green-gold breast shimmering, slipping its needle nose in the zinnia,” is indispensable to the “exercise in supreme attentiveness” that gardening offers.

Frida Kahlo painted a hummingbird into her fiercest self-portrait. Technology historian Steven Johnson drew on hummingbirds as the perfect metaphor for revolutionary innovation. Walt Whitman found great joy and solace in watching a hummingbird “coming and going, daintily balancing and shimmering about,” as he was learning anew how to balance a body coming and going in the world after his paralytic stroke. For poet and gardener Ross Gay, “the hummingbird hovering there with its green-gold breast shimmering, slipping its needle nose in the zinnia,” is indispensable to the “exercise in supreme attentiveness” that gardening offers.

Essential as pollinators and essential as muses to poets, hummingbirds animate every indigenous spiritual mythology of their native habitats and are sold as wearable trinkets on Etsy, to be worn as symbols — of joy, of levity, of magic — by modern secular humans across every imaginable habitat on our improbable planet.

There is, indeed, something almost magical to the creaturely reality of the hummingbird — something not supernatural but supranatural, hovering above the ordinary limits of what biology and physics conspire to render possible.

As if the evolution of ordinary bird flight weren’t miracle enough — scales transfigured into feathers, jaws transfigured into beaks, arms transfigured into wings — the hummingbird, like no other bird among the thousands of known avian species, can fly backward and upside-down, and can hover. It is hovering that most defiantly subverts the standard physics of bird flight: head practically still as the tiny turbine of feather and bone suspends the body mid-air — not by flapping up and down, as wings do in ordinary bird flight, but by swiveling rapidly along the invisible curvature of an infinity symbol. Millions of living, breathing gravity-defying space stations, right here on Earth, capable of slicing through the atmosphere at 385 body-lengths per second — faster than a falcon, faster than the Space Shuttle itself.

That supranatural marvel of nature is what Sy Montgomery — the naturalist who so memorably celebrated the otherworldly marvel of the octopus — celebrates in The Hummingbirds’ Gift: Wonder, Beauty, and Renewal on Wings (public library). She writes:

Alone among the world’s ten thousand avian species, only those in the hummingbird family, Trochilidae, can hover in midair. For centuries, nobody knew how they did it. They were considered pure magic.

[…]

Even the scientists succumbed to hummingbirds’ intoxicating mysteries: they classified them in an order called Apodiformes, which means “without feet” — for it was believed (incorrectly) for many years that a hummingbird had no need for feet. It was thought that no hummingbird ever perched, accounting in part for its sun-washed brilliance: as the comte de Buffon, Georges-Louis Leclerc, wrote in his 1775 Histoire naturelle, “The emerald, the ruby, and the topaz glitter in its garb, which is never soiled with the dust of the earth.”

Science, being the supreme human implement of self-correction, eventually caught up to the reality of the hummingbird’s wispy feet, then unpeeled a thousand subtler and more astonishing realities about the extraordinary feats of which this flying jewel is capable. Read about them here.

FEELING & KNOWING

“A purely disembodied emotion is a nonentity,” William James wrote in his revolutionary theory of how our bodies affect our feelings just before the birth of neuroscience — a science still young, which has already revolutionized our understanding of the cosmos inside the cranium as much as the first century of telescopic astronomy revolutionized our understanding of our place in the universe.

“A purely disembodied emotion is a nonentity,” William James wrote in his revolutionary theory of how our bodies affect our feelings just before the birth of neuroscience — a science still young, which has already revolutionized our understanding of the cosmos inside the cranium as much as the first century of telescopic astronomy revolutionized our understanding of our place in the universe.

Meanwhile, ninety miles inland from William James, while Walt Whitman was redoubling his metaphysical insistence that “the body includes and is the meaning, the main concern… and is the soul,” Emily Dickinson was writing in one of her science-prescient poems:

The Brain — is wider than the Sky —

For — put them side by side —

The one the other will contain

With ease — and you — beside —The Brain is deeper than the sea —

For — hold them — Blue to Blue —

The one the other will absorb —

As sponges — Buckets — do —

It is the task, the destiny of science to concretize with evidence what the poets have always intuited and imagized in abstraction: that we are infinitely more miraculous and infinitely less important than we thought. The universe without, which made us and every star-dusted atom of our consciousness, is ever-vaster and more complex than we suppose it to be; the universe within, which makes the universe without and renders our entire experience of reality through the telescopic lens of our consciousness, is ever-denser and more complex than we suppose it to be.

A century and a half after James, neuroscientist Antonio Damasio picks up an empirical baton where Dickinson had left a torch of intuition. In his revelatory book Feeling & Knowing: Making Minds Conscious (public library), he makes the bold case that consciousness — that ultimate lens of being, which shapes our entire experience of life and makes blue appear blue and gives poems their air of wonder — is not a mental activity confined to the brain but a complex embodied phenomenon governed by the nervous-system activity we call feeling.

Decades after Toni Morrison celebrated the body as the supreme instrument of sanity and self-regard, neuroscience affirms the body as the instrument of feeling that makes the symphony of consciousness possible: feelings, which arise from the dialogue between the body and the nervous system, are not a byproduct of consciousness but made consciousness emerge. (Twenty years earlier — an epoch in the hitherto lifespan of neuroscience — the uncommonly penetrating Martha Nussbaum had anticipated this physiological reality through the lens of philosophy, writing in her superb inquiry into the intelligence of emotions that “emotions are not just the fuel that powers the psychological mechanism of a reasoning creature, they are parts, highly complex and messy parts, of this creature’s reasoning itself.”)

Damasio’s premise rises from the flatland of earlier mind-based theories by a conceptual fulcrum both simple and profound:

Feelings gave birth to consciousness and gifted it generously to the rest of the mind.

Read more here.

OLD GROWTH

Whitman, who considered trees the profoundest teachers in how to best be human, remembered the woman he loved and respected above all others as that rare person who was “entirely herself; as simple as nature; true, honest; beautiful as a tree is tall, leafy, rich, full, free — is a tree.”

Whitman, who considered trees the profoundest teachers in how to best be human, remembered the woman he loved and respected above all others as that rare person who was “entirely herself; as simple as nature; true, honest; beautiful as a tree is tall, leafy, rich, full, free — is a tree.”

Humans, indeed, have a long history of seeing ourselves in trees — fathoming our own nature through theirs, turning to them for lessons in resilience and self-renewal. Hermann Hesse saw in them the paragon of self-actualization, Thoreau reverenced them as cathedrals that consecrate our lives, Dylan Thomas entrusted them with humbling us into the essence of our humanity, ancient mythology placed them at its spiritual center, and science used them as an organizing principle for knowledge.

Our ancient bond with trees as companions and mirrors of our human experience comes alive afresh in Old Growth — a wondrous anthology of essays and poems about trees, culled from the decades-deep archive of Orion Magazine.

With a foreword by the poetic bryologist Robin Wall Kimmerer, and contributions as variegated as Ursula K. Le Guin’s love-poem to trees and arborist William Bryant Logan’s revelatory meditation on immortality and the music of trees, the anthology is a cathedral of wonder and illumination.

—

Published January 28, 2022

—

https://www.themarginalian.org/2022/01/28/favorite-books-2021/

—

ABOUT

CONTACT

SUPPORT

SUBSCRIBE

Newsletter

RSS

CONNECT

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

Tumblr