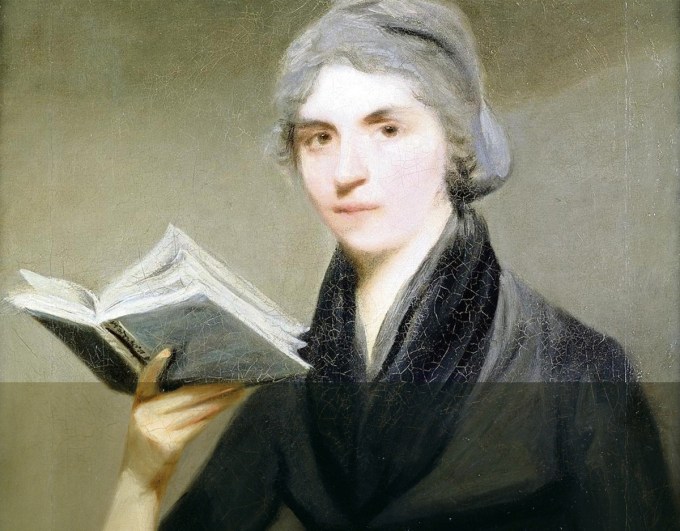

Philosopher Mary Wollstonecraft on the Imagination and Its Seductive Power in Human Relationships

By Maria Popova

“Independence I have long considered as the grand blessing of life, the basis of every virtue,” philosopher and political theorist Mary Wollstonecraft (April 27, 1759–September 10, 1797) wrote in her 1792 proto-feminist masterwork A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, “and independence I will ever secure by contracting my wants, though I were to live on a barren heath.” Independence became the animating force of Wollstonecraft’s life, and there was no form of it she valued more highly than the independence of the imagination — something her second daughter, Frankenstein author Mary Shelley, would come to inherit.

Wollstonecraft saw the imagination as the gateway to liberation, the most vitalizing nectar for the mind, and the most seductive aphrodisiac; she saw love as the domain in which “the imagination mingles its bewitching colouring” — for better or for worse, to enchant into rapture as well as to delude into despair. (A quarter millennium later, philosopher Martha Nussbaum would come to write brilliantly about the imperfect union of the two.)

Wollstonecraft found herself afflicted with “the reveries of a disordered imagination,” which frequently caused her embarrassment and dejection — nowhere more so than in the passions of the heart, which coexisted with equal vigor alongside her formidable intellect.

“The pictures that the imagination draws are so very delightful that we willing[ly] let it predominate over reason till experience forces us to see the truth,” she wrote to her sister in a letter found in The Collected Letters of Mary Wollstonecraft (public library). But a pure love, she believed, was a region “where sincerity and truth will flourish — and the imagination will not dwell on pleasing illusions.”

In December of 1792, shortly after the publication of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman and a month before the execution of Louis XVI furnished a cornerstone of the French Revolution, Wollstonecraft left London for Paris. There, she met and became besotted with the American diplomat, businessman, and adventurer Gilbert Imlay. Although in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman she had renounced sexual passion as complicit in women’s oppression, Imlay awakened in her a magnitude of desire both dissonant with her political views and personally disorienting in far exceeding what she had previously thought herself capable of experiencing.

Wollstonecraft soon became pregnant and gave birth to her first daughter in the spring of 1794, just as Britain was preparing to declare war on France. Imlay had made clear his disinterest in marriage and domesticity but, alarmed by the political turmoil and the danger in which it placed British subjects in Paris, he registered Wollstonecraft as his wife in order to protect her and the baby, even though no legal marriage took place. It was an act more necessary than noble — many of Wollstonecraft’s compatriots in Paris had no such protection and were either arrested or guillotined — but it was also the beginning of the end of their romance. A slow-seething commitment panic began bedeviling Imlay, who eventually left Wollstonecraft heartbroken and alone with an infant amid a raging revolution.

But even in their parting letters, as it becomes clear to Wollstonecraft that her lover wouldn’t return, her beseeching despair is laced with a lucid sense of her unassailable independence. Radiating from them is an awareness of how she had grown infatuated with the fantasy of a man whose reality of character was wholly unworthy of her love. Where her imagination had been the aphrodisiac responsible for her passionate infatuation — a state Julian Fellowes has called “a distortion of reality so remarkable that it should, by rights, enable most of us to understand the other forms of lunacy with the sympathy of fellow-sufferers” — Imlay’s lack of imagination became the agent of disillusionment.

In a letter to Imlay from September of 1794, she makes no apologies about calling out his fatal flaw:

Believe me, sage sir, you have not sufficient respect for the imagination — I could prove to you in a trice that it is the mother of sentiment, the great distinction of our nature, the only purifier of the passions — animals have a portion of reason, and equal, if not more exquisite, senses; but no trace of imagination, or her offspring taste, appears in any of their actions. The impulse of the senses, passions, if you will, and the conclusions of reason, draw men together; but the imagination is the true fire, stolen from heaven, to animate this cold creature of clay, producing all those fine sympathies that lead to rapture, rendering men social by expanding their hearts, instead of leaving them leisure to calculate how many comforts society affords.

In a letter to Imlay from the following June, as his protracted abandonment drags on, she returns to the subject of the imagination and its role in human relationships. With an eye to the perennial question of telling love from lust — a question to which young E.B. White and James Thurber would provide a most delightful answer a century and a half later — and to the role the imagination plays in it, Wollstonecraft writes:

The common run of men, I know, with strong health and gross appetites, must have variety to banish ennui, because the imagination never lends its magic wand to convert appetite into love, cemented by according reason. — Ah! my friend, you know not the ineffable delight, the exquisite pleasure, which arises from a unison of affection and desire, when the whole soul and senses are abandoned to a lively imagination, that renders every emotion delicate and rapturous. Yes; these are emotions, over which satiety has no power, and the recollection of which, even disappointment cannot disenchant; but they do not exist without self-denial.

And yet for all the personal pain that her intense imagination caused her, it was also the wellspring of her creative and intellectual genius — the very thing that rendered her one of the most influential minds of her era. In a sentiment that echoes Anaïs Nin’s assertion that emotional excess is essential for creativity, Wollstonecraft adds:

These emotions, more or less strong, appear to me to be the distinctive characteristic of genius, the foundation of taste, and of that exquisite relish for the beauties of nature, of which the common herd of eaters and drinkers and child-begeters, certainly have no idea… I consider those minds as the most strong and original, whose imagination acts as the stimulus to their senses.

The English political philosopher William Godwin, whom Wollstonecraft married after recovering from the heartbreak with Imlay and who fathered Mary Shelley, would later edit her posthumous works and laud these very letters as having “superiority over the fiction of Goethe” and being “the offspring of a glowing imagination, and a heart penetrated with the passion it essays to describe” — perhaps supreme proof the kind of sincere love Wollstonecraft imagined possible, for Godwin transcended the jealous ego’s knowledge that these letters were written to a former lover and instead celebrated Wollstonecraft for the faculty she valued above all else: her imagination.

Complement this particular portion of The Collected Letters of Mary Wollstonecraft (public library) with Wollstonecraft’s contemporary William Blake’s searing defense of the imagination and pioneering computer programmer Ada Lovelace, whose own ascent as a woman of intellectual accomplishment was shaped by Wollstonecraft’s legacy, on the imagination’s three core faculties.

—

Published January 18, 2017

—

https://www.themarginalian.org/2017/01/18/mary-wollstonecraft-imagination-letters/

—

ABOUT

CONTACT

SUPPORT

SUBSCRIBE

Newsletter

RSS

CONNECT

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

Tumblr