The Universe as an Infinite Storm of Beauty: John Muir on the Transcendent Interconnectedness of Nature

By Maria Popova

“I… a universe of atoms… an atom in the universe,” the Nobel-winning physicist Richard Feynman wrote in his lovely prose poem about the wonder of life. “The fact that we are connected through space and time,” evolutionary biologist Lynn Margulis observed of the interconnectedness of the universe, “shows that life is a unitary phenomenon, no matter how we express that fact.”

A century before Feynman and Margulis, the great Scottish-American naturalist and pioneering environmental philosopher John Muir (April 21, 1838–December 24, 1914) channeled this elemental fact of existence with uncommon poetic might in John Muir: Nature Writings (public library) — a timeless treasure I revisited in composing The Universe in Verse.

Recounting the epiphany he had while hiking Yosemite’s Cathedral Peak for the first time in the summer of his thirtieth year — an epiphany strikingly similar to the one Virginia Woolf had at the moment she understood what it means to be an artist — Muir writes:

When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe. One fancies a heart like our own must be beating in every crystal and cell, and we feel like stopping to speak to the plants and animals as friendly fellow mountaineers. Nature as a poet, an enthusiastic workingman, becomes more and more visible the farther and higher we go; for the mountains are fountains — beginning places, however related to sources beyond mortal ken.

Later that summer, as he makes his way to Tuolumne Meadow in eastern Yosemite, Muir is reanimated with this awareness of the exquisite, poetic interconnectedness of nature, which transcends individual mortality. In a sentiment evocative of Rachel Carson’s lyrical assertion that “the lifespan of a particular plant or animal appears, not as drama complete in itself, but only as a brief interlude in a panorama of endless change,” Muir writes:

One is constantly reminded of the infinite lavishness and fertility of Nature — inexhaustible abundance amid what seems enormous waste. And yet when we look into any of her operations that lie within reach of our minds, we learn that no particle of her material is wasted or worn out. It is eternally flowing from use to use, beauty to yet higher beauty; and we soon cease to lament waste and death, and rather rejoice and exult in the imperishable, unspendable wealth of the universe, and faithfully watch and wait the reappearance of everything that melts and fades and dies about us, feeling sure that its next appearance will be better and more beautiful than the last.

[…]

More and more, in a place like this, we feel ourselves part of wild Nature, kin to everything.

A year earlier, during his famous thousand-mile walk to the Gulf of Mexico, Muir recorded his observations and meditations in a notebook inscribed John Muir, Earth-Planet, Universe. In one of the entries from this notebook, the twenty-nine-year-old Muir counters the human hubris of anthropocentricity in a sentiment far ahead of his time and, in many ways, ahead of our own as we grapple with our responsibility to the natural world. More than a century before Carl Sagan reminded us that we, like all creatures, are “made of starstuff,” Muir humbles us into our proper place in the cosmic order:

The universe would be incomplete without man; but it would also be incomplete without the smallest transmicroscopic creature that dwells beyond our conceitful eyes and knowledge… The fearfully good, the orthodox, of this laborious patchwork of modern civilization cry “Heresy” on every one whose sympathies reach a single hair’s breadth beyond the boundary epidermis of our own species. Not content with taking all of earth, they also claim the celestial country as the only ones who possess the kind of souls for which that imponderable empire was planned.

Long before Maya Angelou reminded us that we are creatures “traveling through casual space, past aloof stars, across the way of indifferent suns,” Muir adds:

This star, our own good earth, made many a successful journey around the heavens ere man was made, and whole kingdoms of creatures enjoyed existence and returned to dust ere man appeared to claim them. After human beings have also played their part in Creation’s plan, they too may disappear without any general burning or extraordinary commotion whatever.

However disquieting and corrosive to the human ego such awareness may be, Muir argues that we can never be conscientious citizens of the universe unless we accept this fundamental cosmic reality. In our chronic civilizational denial of it, we are denying nature itself — we are denying, in consequence, our own humanity. A century before the inception of the modern environmental movement, he writes:

No dogma taught by the present civilization seems to form so insuperable an obstacle in the way of a right understanding of the relations which culture sustains to wildness as that which regards the world as made especially for the uses of man. Every animal, plant, and crystal controverts it in the plainest terms. Yet it is taught from century to century as something ever new and precious, and in the resulting darkness the enormous conceit is allowed to go unchallenged.

I have never yet happened upon a trace of evidence that seemed to show that any one animal was ever made for another as much as it was made for itself. Not that Nature manifests any such thing as selfish isolation. In the making of every animal the presence of every other animal has been recognized. Indeed, every atom in creation may be said to be acquainted with and married to every other, but with universal union there is a division sufficient in degree for the purposes of the most intense individuality; no matter, therefore, what may be the note which any creature forms in the song of existence, it is made first for itself, then more and more remotely for all the world and worlds.

This revelatory sense of interconnectedness comes over Muir again a decade later, as he journeys to British Columbia on a steamer in the spring of 1879, experiencing for the first time the otherworldly wonder and might of the open ocean. A century after William Blake saw the universe in a grain of sand, Muir writes:

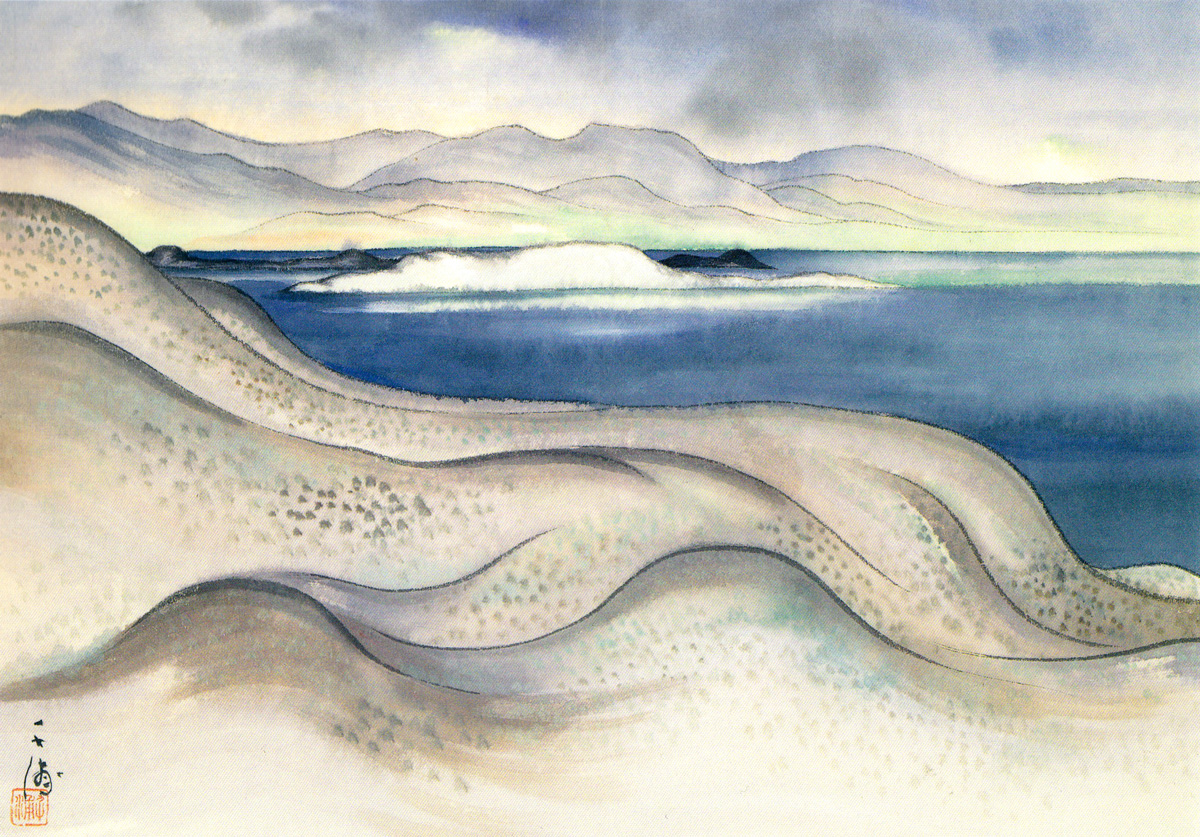

The scenery of the ocean, however sublime in vast expanse, seems far less beautiful to us dry-shod animals than that of the land seen only in comparatively small patches; but when we contemplate the whole globe as one great dewdrop, striped and dotted with continents and islands, flying through space with other stars all singing and shining together as one, the whole universe appears as an infinite storm of beauty.

More than a century later, Muir’s complete Nature Writings remain a transcendent read. Complement this portion with Loren Eiseley on the relationship between nature and human nature and Terry Tempest Williams — a modern-day spiritual heir of Muir’s — on the wilderness as an antidote to the war within ourselves, then revisit Muir’s British contemporary Richard Jefferies on how nature’s beauty dissolves the boundary between us and the world.

—

Published May 10, 2018

—

https://www.themarginalian.org/2018/05/10/john-muir-nature-writings/

—

ABOUT

CONTACT

SUPPORT

SUBSCRIBE

Newsletter

RSS

CONNECT

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

Tumblr