Autumn Light: Pico Iyer on Finding Beauty in Impermanence and Luminosity in Loss

By Maria Popova

Rilke considered winter the season for tending to one’s inner garden. A century after him, Adam Gopnik reverenced the bleakest season as a necessary counterpoint to the electricity of spring, harmonizing the completeness of the world and helping us better appreciate its beauty — without winter, he argued, “we would be playing life with no flats or sharps, on a piano with no black keys.”

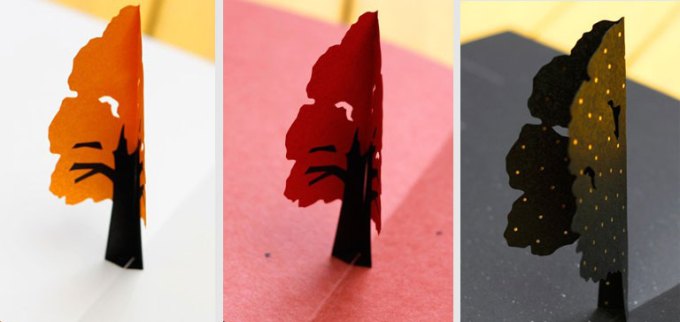

What, then, of autumn — that liminal space between beauty and bleakness, foreboding and bittersweet, yet lovely in its own way? Colette, in her meditation on the splendor of autumn and the autumn of life, celebrated it as a beginning rather than a decline. But perhaps it is neither — perhaps, between its falling leaves and fading light, it is not a movement toward gain or loss but an invitation to attentive stillness and absolute presence, reminding us to cherish the beauty of life not despite its perishability but precisely because of it; because the impermanence of things — of seasons and lifetimes and galaxies and loves — is what confers preciousness and sweetness upon them.

So argues Pico Iyer, one of the most soulful and perceptive writers of our time, in Autumn Light: Season of Fire and Farewells (public library).

Having spent a long stretch of life in bicultural seasonality, traveling between the California home of his octogenarian mother and the Japanese home he has made with his wife Hiroko, Iyer reflects on what the country of his heart — home to the beautiful philosophy of wabi-sabi — has taught him about the heart’s seasons:

I long to be in Japan in the autumn. For much of the year, my job, reporting on foreign conflicts and globalism on a human scale, forces me out onto the road; and with my mother in her eighties, living alone in the hills of California, I need to be there much of the time, too. But I try each year to be back in Japan for the season of fire and farewells. Cherry blossoms, pretty and frothy as schoolgirls’ giggles, are the face the country likes to present to the world, all pink and white eroticism; but it’s the reddening of the maple leaves under a blaze of ceramic-blue skies that is the place’s secret heart.

We cherish things, Japan has always known, precisely because they cannot last; it’s their frailty that adds sweetness to their beauty. In the central literary text of the land, The Tale of Genji, the word for “impermanence” is used more than a thousand times, and bright, amorous Prince Genji is said to be “a handsomer man in sorrow than in happiness.” Beauty, the foremost Jungian in Japan has observed, “is completed only if we accept the fact of death.” Autumn poses the question we all have to live with: How to hold on to the things we love even though we know that we and they are dying. How to see the world as it is, yet find light within that truth.

The sudden death of Iyer’s father-in-law focuses that existential light to a burning beam and pulls him, unseasonably, to Japan in the flaming height of autumn, to the small wooden house where his wife’s parents lived and loved for half a century. With the suprasensory porousness to life that the death of a loved one gives us, Iyer travels across time and space, to another season and another loss in the California wildfires, and writes:

Everything is burning now, though the days have lost little in clarity or warmth. The leaves are scraps of flame, the hills electric with color; as we fall into December, everything is ready to be reduced to ash. From the windows of the health club, I see bonfires sending smoke above the gas stations; I walk up through magic-hour streets and wonder how long these days of gold can last.

It still has the capacity to chill me: the memory of the flames tearing through the black hillsides all around as I drove down after forty-five minutes of watching our family home, some years ago, reduced to cinders. Death paying a house call; and then, when the house was rebuilt on its perilous ridge — where my mother sleeps right now — again and again, new fires rising all around it. One time after another, we receive the reverse-911 call telling us we have to leave right now, and we stuff a few valuables in the car, then watch, from downtown, as the sky above our home turns a coughy black, the sun pulsing like an electrified orange in the heavens.

Between terror and transcendence, between epochs and cultures, Iyer locates the common hearth of human experience:

“Everything must burn,” wrote my secret companion Thomas Merton, as he walked around his silent monastery in the dark, on fire watch. “Everything must burn, my monks,” the Buddha said in his “Fire Sermon”; life itself is a burning house, and soon that body you’re holding will be bones, that face that so moves you a grinning skull. The main temple in Nara has burned and come back and burned and come back, three times over the centuries; the imperial compound, covering a sixth of all Kyoto, has had to be rebuilt fourteen times. What do we have to hold on to? Only the certainty that nothing will go according to design; our hopes are newly built wooden houses, sturdy until someone drops a cigarette or match.

He time-travels once again to several years earlier, when his father-in-law had just turned ninety and Japan had just suffered one of the most devastating disasters in recorded history, to wrest from a moment of life beautiful affirmation for Mary Oliver’s Blake- and Whitman-inspired insistence that “all eternity is in the moment”:

I glance at Hiroko’s watch; later this afternoon, I’ll have to drop the aging couple at their home, and take the rented car to Kyoto Station. Then a six-hour trip, via a series of bullet trains, up to a broken little town in Fukushima, where a nuclear plant melted down after the tsunami seven months ago.

A war photographer is waiting for me there, and we’re going to talk to some of the workers who are risking their lives to go into the poisoned area to try to repair the plant, and ask them why they’re doing it. How learn to live with what you can never control?

For now, though, there’s nowhere to go on the silent mountain, and a boy who’s just turned ninety is surveying the landscape with the rapt eagerness of an Eagle Scout, while his wife of sixty years sings, “We’re so lucky to have a long life!”

Hold this moment forever, I tell myself; it may never come again.

Complement Iyer’s exquisite Autumn Light with physicist and poet Alan Lightman on reconciling our yearning for permanence with a universe predicated on constant change, Marcus Aurelius on the key to living with presence while facing our mortality, and Italian artist Alessandro Sanna’s watercolor love letter to seasonality, then revisit Iyer on what Leonard Cohen taught him about the art of stillness.

—

Published October 11, 2019

—

https://www.themarginalian.org/2019/10/11/autumn-light-pico-iyer/

—

ABOUT

CONTACT

SUPPORT

SUBSCRIBE

Newsletter

RSS

CONNECT

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

Tumblr