Ronald McNair’s Civil Disobedience: The Illustrated Story of How a Little Boy Who Grew Up to Be a Trailblazing Astronaut Fought Segregation at the Public Library

By Maria Popova

“Knowledge sets us free… A great library is freedom,” Ursula K. Le Guin wrote in contemplating the sacredness of public libraries. “Freedom is not something that anybody can be given; freedom is something people take and people are as free as they want to be,” her contemporary James Baldwin — who had read his way from the Harlem public library to the literary pantheon — insisted in his courageous and countercultural perspective on freedom.

Ronald McNair (October 21, 1950–January 28, 1986) was nine when he took his freedom into his own small hands.

Unlike Maya Angelou, who credited a library with saving her life, McNair’s triumphant and tragic life could not have been saved even by a library — he was the age I am now when he perished aboard the Space Shuttle Challenger before the eyes of a disbelieving nation. But his life was largely made by a library — a life equal parts inspiring and improbable against the cultural constrictions of his time and place; a life of determination that rendered him the second black person to launch into space, a decade and a half after a visionary children’s book first dared imagine the possibility.

A quarter century after McNair’s untimely death, a contemporary children’s book set out to broaden the landscape of possibility for generations to come by celebrating the formative fortitude of his trailblazing life.

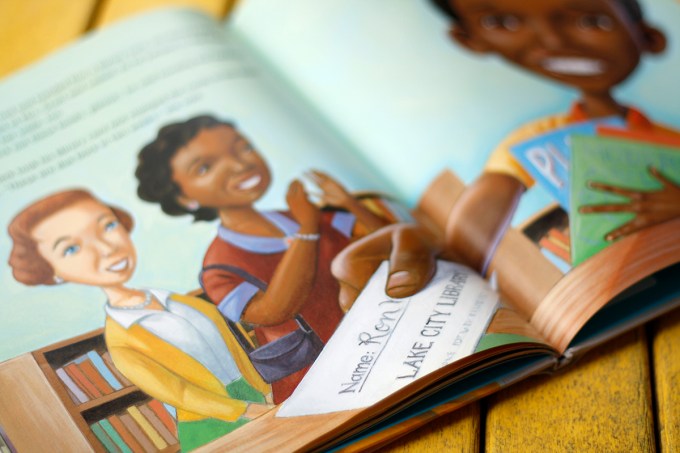

Ron’s Big Mission (public library) by lyricist, scriptwriter, and teacher Rose Blue and former U.S. Navy journalist Corinne J. Naden, illustrated by Don Tate — a lovely addition to these emboldening picture-book biographies of cultural heroes — tells the story of a summer day in the segregated South in 1959 when the young Ron, a voracious reader with a passion for airplanes and dreams of becoming a pilot, awakens with the daring determination to bring home a book from the library checked out under his own name. He knows this is not allowed — he has devoured countless books at the library, but he knows that only white people are allowed to check them out. He also knows, with the clarity that children have in seeing into the unalloyed heart of reality, that whatever justification the grownups in power might have for this rule, there is no justice and humanity in it.

On the wings of his purehearted enthusiasm to dismantle the hypocrisies of the system, Ron races past the local baker offering him a fresh-baked donut, past his friend Carl shooting hoops, and into the library as the day’s first visitor.

The head librarian greets him warmly, delighted to see the young reader who has become “her best customer.” Ron waves back and heads straight for the shelves. After the usual disappointment of finding hardly any books with children who look like him, he opts for the impersonal consolation of machines, pulling out a few books about airplanes.

When another regular patron of the library — a kindly older white lady — offers to check the books out for him, Ron thanks her but declines. He heads to the front desk and lays the books on the counter. The desk clerk doesn’t even look at him.

With a child’s benevolence of interpretation, he thinks at first that she simply hasn’t heard him. But when she continues to disregard him, he does the most logical thing, by the undiluted logic we adults have relinquished in favor of the polite pretensions we call propriety: He jumps on the counter, then calmly restates his wish to check out the books.

Everyone is aghast.

Ron is reminded of the rule.

Still polite but still standing on the counter, he simply restates his wish — a small boy’s enormous act that would have made Thoreau proud as America’s premier champion of civil disobedience and ardent lover of public libraries.

Other patrons are staring. The library staff are stumped. Finally, they call the police. Two policemen arrive immediately. “Let someone check out the books for you, son,” one of them pleads with Ron. Ron refuses.

The head librarian then turns to the ultimate authority — Ron’s mother.

When Mrs. McNair arrives, she too reminds Ron of the rule — the rule he has known all along, the rule that is not a matter of reminding but of resisting. When this nine-year-old revolutionary states simply that the rule is wrong and unfair, and asks why he can’t check out books like everyone else, all the adults look at each other and grow silent.

The head librarian stares into the empty space as pandemonium enfolds the empty rule, then looks at Ron — this largehearted, hardheaded, hungry-brained boy, her very best customer. And she knows instantly what she must do.

In a testament to Hannah Arendt’s superb contemporaneous inquiry into the only effective antidote to the normalization of evil and her insistence that “under conditions of terror most people will comply but some people will not [and] no more is required, and no more can reasonably be asked, for this planet to remain a place fit for human habitation,” the librarian disappears into her office as Mrs. McNair and the policemen continue trying to sway Ron.

When she emerges a few minutes later, she hands Ron a library card with his very own name on it. Beaming with his triumph and with gratitude to his sole ally in this act of resistance on the small scale of the personal, with the colossal stakes of the political, he hands the card to the desk clerk as he politely restates his wish to check out the books.

She stamps it.

The rest is history, and it is the making of a future — Ron’s own future as a trailblazer who devoted his life to the ultimate unifying force, our shared cosmic belonging, and the futures of generations for whom he modeled the courage of rewriting the dominant narrative of permission and possibility. Today, a Space Shuttle graces the mural on the walls of the children’s room at the Lake City public library in South Carolina, where all children are allowed to check out any book they wish, including books starring children who look a lot like them.

Complement Ron’s Big Mission with What Miss Mitchell Saw — a lyrical picture-book about astronomer Maria Mitchell, who blazed the way for women in science — and a moving remembrance of Ronald McNair by his brother, then revisit astronaut Leland Melvin — the thirteenth black astronaut to leave Earth’s atmosphere, and among the fraction of a fraction of one percent of our species to have seen the splendor of our planet’s canopy from space — reading Pablo Neruda’s love letter to the forest.

For other picture-book biographies of visionaries who have changed the way we understand and live life, savor the illustrated stories of Wangari Maathai, Ada Lovelace, Louise Bourgeois, Jane Goodall, Jane Jacobs, John Lewis, Frida Kahlo, E.E. Cummings, Louis Braille, Pablo Neruda, Albert Einstein, Muddy Waters, and Nellie Bly.

—

Published June 5, 2020

—

https://www.themarginalian.org/2020/06/05/rons-big-mission/

—

ABOUT

CONTACT

SUPPORT

SUBSCRIBE

Newsletter

RSS

CONNECT

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

Tumblr