The Loveliest Children’s Books of 2021

By Maria Popova

Great children’s books are works of existential philosophy in disguise — gifts of timeless consolation for the eternal child living in each of us, on the pages of which some of the most visionary minds of every era are formed. This I have long believed. But I had not, until a recent reckoning with this here fifteen-year body of work and love, realized what a reliable barometer of my state of being children’s books are — the dual hindsight of autobiographical memory and my archive of writing reveals a strong positive correlation between how many children’s books I enjoyed in any given year and my general level of wellbeing that year.

This year — the year my own (first) such book met the world — I read very few: partly because my native taste for the timeless, the cosmic, the planetary, the beyond-human was largely unfed by the year’s buffet of books with human-centric, of-the-moment themes sacrificing the poetic at the altar of the politicized; partly a reflection of my human state of being.

Here are a handful I wrote about this year and loved with all my heart — a list of loves partial in both senses of the word and invariably incomplete, given the limitations of any one person’s finitude of time and singularity of thought.

THE BOY WHOSE HEAD WAS FILLED WITH STARS

In 1908, Henrietta Swan Leavitt — one of the women known as the Harvard Computers, who revolutionized astronomy long before they could vote — was analyzing photographic plates at the Harvard College Observatory to measure and catalogue the brightness of stars when she began noticing a consistent correlation between the luminosity of a class of variable stars and their pulsation period, between their brightness and their blinking pattern.

In 1908, Henrietta Swan Leavitt — one of the women known as the Harvard Computers, who revolutionized astronomy long before they could vote — was analyzing photographic plates at the Harvard College Observatory to measure and catalogue the brightness of stars when she began noticing a consistent correlation between the luminosity of a class of variable stars and their pulsation period, between their brightness and their blinking pattern.

At the same time, a dutiful boy cusping on manhood was repressing his childhood love of astronomy and beginning his legal studies to fulfill his dying father’s demand for an ordinary, reputable life. Upon his father’s death, Edwin Hubble (November 20, 1889–September 28, 1953) would unleash his passion for the stars into a formal study of astronomy. After the interruption of a world war, he would lean on Leavitt’s data to upend millennia of cosmic parochialism, demonstrating two revolutionary facts about the universe: that it is tremendously bigger than we thought, and that it is getting bigger by the blink. The law underlying its expansion would come to bear his name, as would the ambitious space telescope that would give humanity an unprecedented glimpse of a cosmos “so brutal and alive it seemed to comprehend us back.”

Hubble’s Law staggers the imagination with the awareness that even our most intimate celestial companion, the Moon, is slowly moving away from us every day, about as fast as your fingernails grow. This means that at some future point, the greatest cosmic spectacle visible from Earth will be no more, for a total solar eclipse is a function of the glorious accident that the Moon is at just the right distance for its shadow to cover the entire face of the Sun when passing before it from our vantage point — a shadow that will grow smaller and smaller as our satellite drifts farther and farther away. Before Hubble, the study of astronomy had already stunned the human mind with the awareness that this entire drama of life is a miracle of chance, unfolding on a common rocky planet tossed at just the right distance from its star to have the optimal temperature and optimal atmosphere for supporting life. Hubble sent the human mind spinning with the swirl of gratitude and terror at the awareness that it is all a temporary miracle.

Author Isabelle Marinov and artist Deborah Marcero pay tender homage to Hubble’s life and legacy in The Boy Whose Head Was Filled with Stars: A Life of Edwin Hubble (public library) — a splendid addition to the finest picture-book biographies of revolutionary minds, and one particularly dear to my own heart in light of my ongoing devotion to building New York City’s first public observatory to cast the cosmic enchantment on future Hubbles and Leavitts, to make life more livable for the rest of us by inviting the telescopic perspective.

Peek inside here.

BEFORE I GREW UP

Childhood is one great brush-stroke of loneliness, thick and pastel-colored, its edges blurring out into the whole landscape of life.

Childhood is one great brush-stroke of loneliness, thick and pastel-colored, its edges blurring out into the whole landscape of life.

In this blur of being by ourselves, we learn to be ourselves. One measure of maturity might be how well we grow to transmute that elemental loneliness into the “fruitful monotony” Bertrand Russell placed at the heart of our flourishing, the “fertile solitude” Adam Phillips recognized as the pulse-beat of our creative power.

If we are lucky enough, or perhaps lonely enough, we learn to reach out from this primal loneliness to other lonelinesses — Neruda’s hand through the fence, Kafka’s “hand outstretched in the darkness” — in that great gesture of connection we call art.

Rilke, contemplating the lonely patience of creative work that every artist knows in their marrow, captured this in his lamentation that “works of art are of an infinite loneliness” — Rilke, who all his life celebrated solitude as the groundwater of love and creativity, and who so ardently believed that to devote yourself to art, you must not “let your solitude obscure the presence of something within it that wants to emerge.”

Giuliano Cucco (1929–2006) was still a boy, living with his parents amid the majestic solitudes of rural Italy, when the common loneliness of childhood pressed against his uncommon gift and the artistic impulse began to emerge, tender and tectonic.

Over the decades that followed, he grew volcanic with painting and poetry, with photographs and pastels, with art ablaze with a luminous love of life.

When Cucco moved to Rome as a young artist, he met the young American nature writer John Miller. A beautiful friendship came abloom. Those were the early 1960, when Rachel Carson — the poet laureate of nature writing — had just awakened the modern ecological conscience and was using her hard-earned stature to issue the radical insistence that children’s sense of wonder is the key to conservation.

Into this cultural atmosphere, Cucco and Miller joined their gifts to create a series of stunning and soulful nature-inspired children’s books.

But when Miller returned to New York, door after door shut in his face — commercial publishers were unwilling to invest in the then-costly reproduction of Cucco’s vibrant art. It took half a century of countercultural courage and Moore’s law for Brooklyn-based independent powerhouse Enchanted Lion to take a risk on these forgotten vintage treasures and bring them to life.

Eager to reconnect with his old friend and share the exuberant news, Miller endeavored to track down Cucco’s family. But when he finally reached them after a long search, he was devastated to learn that the artist and his wife had been killed by a motor scooter speeding through a pedestrian crossing in Rome. Their son had just begun making his way through a trove of his father’s paintings — many unseen by the world, many depicting the landscapes and dreamscapes of childhood that shaped his art.

Because grief is so often our portal to beauty and aliveness, Miller set out to honor his friend by bringing his story to life in an uncommonly original and tender way — traveling back in time on the wings of memory and imagination, to the lush and lonesome childhood in which the artist’s gift was forged, projecting himself into the boy’s heart and mind through the grown man’s surviving paintings, blurring fact and fancy.

Before I Grew Up (public library) was born — part elegy and part exultation, reverencing the vibrancy of life: the life of feeling and of the imagination, the life of landscape and of light, the life of nature and of the impulse for beauty that irradiates what is truest and most beautiful about human nature.

Peek inside here.

THE TREE IN ME

Walt Whitman, who considered trees the profoundest teachers in how to best be human, remembered the woman he loved and respected above all others as that rare person who was “entirely herself; as simple as nature; true, honest; beautiful as a tree is tall, leafy, rich, full, free — is a tree.”

Walt Whitman, who considered trees the profoundest teachers in how to best be human, remembered the woman he loved and respected above all others as that rare person who was “entirely herself; as simple as nature; true, honest; beautiful as a tree is tall, leafy, rich, full, free — is a tree.”

At the outset of what was to become the most challenging year of my life, and the most challenging for the totality of the world in our shared lifetime, I resolved to face it like a tree — a resolution blind to that unfathomable future, as all resolutions and all futures tend to be, but one that made it infinitely more survivable. I was not the only one. Humans, after all, have a long history of learning resilience from trees and fathoming our own nature through theirs: Hesse saw in them the paragon of self-actualization, Thoreau reverenced them as cathedrals that consecrate our lives, Dylan Thomas entrusted them with humbling us into the essence of our humanity, ancient mythology placed them at its spiritual center, and science used them as an organizing principle for knowledge.

Artist and author Corinna Luyken draws on this intimate connection between the sylvan and the human in The Tree in Me (public library) — a lyrical meditation on the root of creativity, strength, and connection, with a spirit and sensibility kindred to her earlier emotional intelligence primer in the form of a painted poem.

Inspired by Thich Nhat Hanh’s timeless and transformative mindfulness teachings, which she first encountered long ago in the character-kiln of adolescence and which profoundly influenced her worldview as she matured, Luyken considers the book “a seedling off the tree” from the great Zen teacher’s classic tangerine meditation — the fruition of her longtime desire to make something beautiful and tender that invites the young (and not only the young) to look more deeply into the nature of the world, into their own nature and its magnificent interconnectedness to all of nature. After years of incubation, after many trials that landed far from her vision, a spare poem came to her. Paintings grew out of the words. A book blossomed.

Peek inside here.

WHAT IS A RIVER

“There is a mystery about rivers that draws us to them, for they rise from hidden places and travel by routes that are not always tomorrow where they might be today,” Olivia Laing wrote in her stunning meditation on life, loss, and the wisdom of rivers after she walked the River Ouse from source to sea — the River Ouse, in which Virginia Woolf slipped out of the mystery of life, having once observed that “the past only comes back when the present runs so smoothly that it is like the sliding surface of a deep river.”

“There is a mystery about rivers that draws us to them, for they rise from hidden places and travel by routes that are not always tomorrow where they might be today,” Olivia Laing wrote in her stunning meditation on life, loss, and the wisdom of rivers after she walked the River Ouse from source to sea — the River Ouse, in which Virginia Woolf slipped out of the mystery of life, having once observed that “the past only comes back when the present runs so smoothly that it is like the sliding surface of a deep river.”

Rivers are the crucible of human civilization, pulsating with the might and mystery of water, their serpentine paths encoded with the precision of pi, their ceaseless flow encoded in our greatest poems.

“Time is a river that sweeps me along, but I am the river,” Borges wrote in his timeless refutation of time.

But what is a river?

That is what Lithuanian illustrator and storyteller Monika Vaicenavičienė contemplates in What Is a River? (public library) — part prose poem and part encyclopedia, exploring the many things a river is and can be, ecologically and existentially.

The story begins on the banks of a river, with a little girl picking flowers — “every flower has a meaning” — and watching her grandmother sew. What unfolds is framed as the grandmother’s answer to the girl’s question of what a river is:

A river is a thread.

It embroiders our wold with beautiful patterns.

It connects people and places, past and present.

It stitches stories together.

Myth and fact, Geology and history converge into a larger lyrical reflection on the ceaseless flow of existence, linking the Ancient Greek myth of Oceanus — the great river encircling the Earth, from which the word ocean derives — with the ecological reality of Earth’s immense, interconnected, ancient system of water circulating through the atmosphere and pulsating through the biosphere.

Peek inside here.

SEEKING AN AURORA

In 1621, already questioning his life in the priesthood — the era’s safest and most reputable career for the educated — the 29-year-old Pierre Gassendi, a mathematical prodigy since childhood, traveled to the Arctic circle as he began diverting his passionate erudition toward Aristotelian philosophy and astronomy. There, under the polar skies, he witnessed an otherworldly spectacle on Earth — our planet’s most intimate and dramatic contact with its home star, a chromatic swirl of the ephemeral and the eternal unloosed as solar winds blow millions of charged particles from the Sun across the orrery of the Solar System and into Earth’s atmosphere, where our magnetic fields carry them toward the poles. As they collide with the particles of different atmospheric gasses, they ionize and discharge energy as photons of different colors — red, blue, green, and violent — painting the nocturne with the waking dream of a pastel-technicolor dawn.

In 1621, already questioning his life in the priesthood — the era’s safest and most reputable career for the educated — the 29-year-old Pierre Gassendi, a mathematical prodigy since childhood, traveled to the Arctic circle as he began diverting his passionate erudition toward Aristotelian philosophy and astronomy. There, under the polar skies, he witnessed an otherworldly spectacle on Earth — our planet’s most intimate and dramatic contact with its home star, a chromatic swirl of the ephemeral and the eternal unloosed as solar winds blow millions of charged particles from the Sun across the orrery of the Solar System and into Earth’s atmosphere, where our magnetic fields carry them toward the poles. As they collide with the particles of different atmospheric gasses, they ionize and discharge energy as photons of different colors — red, blue, green, and violent — painting the nocturne with the waking dream of a pastel-technicolor dawn.

Awestruck with the natural poetry and the mythic feeling-tone of the luminous spectacle, Gassendi named what he saw Aurora borealis — after Aurora, the Roman goddess of dawn, and borealis, the Latin word for “northern.” Eventually, as explorers braved the icy oceanic expanses to visit the polar regions of the Southern hemisphere over the following centuries, they adapted Gassendi’s etymology to name the Antarctic version of the luminous display Aurora australis, after the Latin word for “southern.”

From the land of Aurora australis comes Seeking an Aurora (public library) — a work of transcendence and tenderness by New Zealand author-artist duo Elizabeth Pulford and Anne Bannock, whose spare poetic prose and soulful paintings interleave to enlush an inner landscape of wonder, suspended between the creaturely and the cosmic.

Peek inside here.

DARLING BABY

“The secret of success,” Jackson Pollock’s father wrote to the teenage artist-to-be in his wonderful letter of life-advice, “is to be fully awake to everything about you.” Few things beckon our attention and awaken us to life more compellingly than color. “Our lives, when we pay attention to light, compel us to empathy with color,” Ellen Meloy wrote in her exquisite meditation on the chemistry, culture, and the conscience of color. And why else live if not to pay attention to the changing light?

“The secret of success,” Jackson Pollock’s father wrote to the teenage artist-to-be in his wonderful letter of life-advice, “is to be fully awake to everything about you.” Few things beckon our attention and awaken us to life more compellingly than color. “Our lives, when we pay attention to light, compel us to empathy with color,” Ellen Meloy wrote in her exquisite meditation on the chemistry, culture, and the conscience of color. And why else live if not to pay attention to the changing light?

In Darling Baby (public library), artist Maira Kalman, a poet of chromatic tenderness, composes an uncommon ode to aliveness, to the vibrant beauty of life, life that is very new and life that is very old.

As she teaches the baby to look at this color, this shape, this quality of light, we see the grownup relearn to see with those baby-eyes that are awake to the luminous everythingness of everything, undulled by the accumulation of filters we call growing up. What emerges is a celebration of attention as affirmation of aliveness, a vibrant testament to Simone Weil’s exquisite observation that “attention is the rarest and purest form of generosity.” Page after painted page, a generous presence unfolds — presence with the new life of this small helpless observer of the world, presence with the ancient life of sky and sea.

Peek inside here.

MAKE MEATBALLS SING

When Matthew Burgess was an eleven-year-old already feeling other in the suburban Southern California of his childhood — long before he became a poet and a public school art teacher, before he made a bicontinental home in Brooklyn and Berlin with his husband — he was captivated by a tiny bright-spirited rainbow on a postage stamp that appeared on the television show The Love Boat. It was the now-iconic 1985 USPS Love stamp — a miniature of the largest copyrighted artwork in the world: the colossal rainbow swash painted on a Boston gas storage tank in 1971 by Corita Kent (November 20, 1918–September 18, 1986) — the radical nun, artist, teacher, social justice activist, and long-undersung pop art pioneer, who inspired generations of makers with her 10 rules for learning and life, collaborated frequently and dazzlingly with poets, believed that “the person who makes things is a sign of hope,” and made her art and her life along the vector of this belief.

When Matthew Burgess was an eleven-year-old already feeling other in the suburban Southern California of his childhood — long before he became a poet and a public school art teacher, before he made a bicontinental home in Brooklyn and Berlin with his husband — he was captivated by a tiny bright-spirited rainbow on a postage stamp that appeared on the television show The Love Boat. It was the now-iconic 1985 USPS Love stamp — a miniature of the largest copyrighted artwork in the world: the colossal rainbow swash painted on a Boston gas storage tank in 1971 by Corita Kent (November 20, 1918–September 18, 1986) — the radical nun, artist, teacher, social justice activist, and long-undersung pop art pioneer, who inspired generations of makers with her 10 rules for learning and life, collaborated frequently and dazzlingly with poets, believed that “the person who makes things is a sign of hope,” and made her art and her life along the vector of this belief.

This sentiment — the most precise and poetic summation of Sister Corita’s credo — is the epigraph that opens Burgess’s loving picture-book biography Make Meatballs Sing: The Life and Art of Corita Kent (public library), created in collaboration with the Corita Art Center and illustrated by artist Kara Kramer with patterned, textured, sensitive vibrancy consonant with Corita’s art spirit and sensibility.

Doing and making are acts of hope, and as that hope grows we stop feeling overwhelmed by the troubles of the world. We remember that we — as individuals and groups — can do something about those troubles.

Emerging from these tender pages is an activist who devoted her life to fighting with fierce gentleness and generosity of soul for justice and peace in every form, from civil rights to nuclear disarmament; a rebel who subverted commerce for creativity, turning a corporate slogan (for Del Monte tomato sauce) into a clarion call for the the power of art to constellate the ordinary with wonder (which lent the book its title); a visionary who subverted the outdated dogmas of the very institution she served to effect landmark reform within the Catholic Church and to engage the secular world with the creative life of the soul; a teacher who helped her students overcome the self-consciousness and overthinking that stifle creativity by fusing play and work through her quirkily titled, ingeniously deployed process of PLORKing; an artist who became a patron saint of noticing, of paying closer attention to the world as the only means of loving it more fully — something Corita herself captured in an essays on art and life:

Poets and artists — makers — look long and lovingly at commonplace things, rearrange them and put their rearrangements where others can notice them too.

Peek inside here.

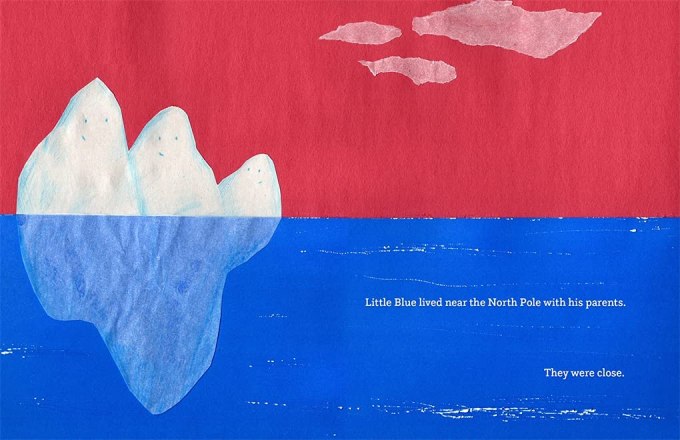

BLUE FLOATS AWAY

“The things we want are transformative, and we don’t know or only think we know what is on the other side of that transformation,” Rebecca Solnit wrote in her unsurpassable Field Guide to Getting Lost.

“The things we want are transformative, and we don’t know or only think we know what is on the other side of that transformation,” Rebecca Solnit wrote in her unsurpassable Field Guide to Getting Lost.

This might be the greatest challenge of our consciousness — that when life beckons us to broaden our inner landscapes of possibility, it calls on us to choose experiences the transformative power of which we might not be able to recognize and desire with the yet-untransformed self, and so we might not choose to have them. (Philosophers have explored this paradoxical blind spot to transformative experiences in an elegant thought experiment known as the vampire problem.)

But this might also be the most hopeful aspect of our consciousness — that we know ourselves only incompletely; that the life we have is only a subset of our possible life; that we are capable of having experiences which profoundly transform how we live our lives in this house of sinew and soul, transforming in the process the very texture of who we believe ourselves to be.

This paradox of transformation comes alive with uncommon tenderness, through a singular lens — the science and poetics of Earth’s water cycle — in Blue Floats Away (public library) by Travis Jonker, an elementary school librarian by day and an author by night, and Grant Snider, an orthodontist by day and an artist (yes, that artist) by night.

Peek inside here.

(AND FROM ME: THE SNAIL WITH THE RIGHT HEART)

Great children’s books move young hearts, yes, but they also move the great common heart that beats in the chest of humanity by articulating in the language of children, which is the language of simplicity and absolute sincerity, the elemental truths of being: what it means to love, what it means to be mortal, what it means to live with our fragilities and our frissons. As such, children’s books are miniature works of philosophy, works of wonder and wonderment that bypass our ordinary resistances and our cerebral modes of understanding, entering the backdoor of consciousness with their soft, surefooted gait to remind us who and what we are.

Great children’s books move young hearts, yes, but they also move the great common heart that beats in the chest of humanity by articulating in the language of children, which is the language of simplicity and absolute sincerity, the elemental truths of being: what it means to love, what it means to be mortal, what it means to live with our fragilities and our frissons. As such, children’s books are miniature works of philosophy, works of wonder and wonderment that bypass our ordinary resistances and our cerebral modes of understanding, entering the backdoor of consciousness with their soft, surefooted gait to remind us who and what we are.

This is something I have always believed, and so I have always turned to children’s books — classics like The Little Prince, which I reread once a year every year for basic soul-maintenance, and modern masterpieces like Cry, Heart, But Never Break — as mighty instruments of existential calibration. But I never thought I would write one.

And then I did: The Snail with the Right Heart: A True Story (public library) is a labor of love three years in the making, illustrated by the uncommonly talented and sensitive Ping Zhu, whom I asked for the honor after she staggered me with the painting that became the cover of A Velocity of Being: Letters to a Young Reader.

While the story is inspired by a beloved young human in my own life, who is living with the same rare and wondrous variation of body as the real-life mollusk protagonist, it is a larger story about science and the poetry of existence, about time and chance, genetics and gender, love and death, evolution and infinity — concepts often too abstract for the human mind to fathom, often more accessible to the young imagination; concepts made fathomable in the concrete, finite life of one tiny, unusual creature dwelling in a pile of compost amid an English garden.

At the heart of the story, excerpted here, is an invitation not to mistake difference for defect and to recognize, across the accordion scales of time and space, diversity as nature’s fulcrum of resilience and wellspring of beauty.

Peek inside, and read the story, here.

* * *

For other timelessly wondrous children’s books, savor these favorites from years past.

—

Published December 19, 2021

—

https://www.themarginalian.org/2021/12/19/best-childrens-books-2021/

—

ABOUT

CONTACT

SUPPORT

SUBSCRIBE

Newsletter

RSS

CONNECT

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

Tumblr